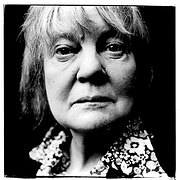

Iris Murdoch (1919–1999)

Author of The Sea, the Sea

About the Author

Iris Murdoch was one of the twentieth century's most prominent novelists, winner of the Booker Prize for The Sea. She died in 1999. (Publisher Provided) Iris Murdoch was born in Dublin, Ireland on July 15, 1919. She was educated at Badminton School in Bristol and Oxford University, where she read show more classics, ancient history, and philosophy. After several government jobs, she returned to academic life, studying philosophy at Newnham College, Cambridge. In 1948, she became a fellow and tutor at St. Anne's College, Oxford. She also taught at the Royal College of Art in London. A professional philosopher, she began writing novels as a hobby, but quickly established herself as a genuine literary talent. She wrote over 25 novels during her lifetime including Under the Net, A Severed Head, The Unicorn, and Of the Nice and the Good. She won several awards including the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for The Black Prince in 1973 and the Booker Prize for The Sea, The Sea in 1978. She died on February 8, 1999 at the age of 79. (Bowker Author Biography) show less

Image credit: © Steve Pyke 1990 (use of image requires permission from Steve Pyke)

Works by Iris Murdoch

The Fire and the Sun: Why Plato Banished the Artists. Based upon the Romanes Lecture (Oxford Paperbacks) (1977) 117 copies

The Novels of Iris Murdoch Volume Two: The Flight from the Enchanter, The Red and the Green, and The Time of the Angels (2018) 9 copies

The Novels of Iris Murdoch Volume One: Henry and Cato, The Italian Girl, and The Philosopher's Pupil (2018) 9 copies

The Novels of Iris Murdoch Volume Three: A Word Child, An Unofficial Rose, and Bruno's Dream (2018) 6 copies

La salvación por las palabras : ¿puede la literatura curarnos de los males de la filosofía? (2014) 6 copies

O Sino 4 copies

Canterburyjske priče 4 copies

Hoe bewijs ik het bestaan van God 2 copies

Unicórnio 1 copy

Ο Μαύρος Πρίγκηπας 1 copy

Een filosofie van de liefde 1 copy

Henry e Cato 1 copy

Przypadkowy cz¿owiek 1 copy

İTALYAN KIZI 1 copy

Tilfælghedens spil 1 copy

[Notebook : 34 pages occupied with lists of words in Russian with their English translations] 1 copy

[Make a joyful noise Vol. 2] 1 copy

[Make a joyful noise Vol. 1] 1 copy

Hver tar sin 1 copy

Murdoch, Iris Archive 1 copy

Against Dryness 1 copy

Os Olhos da Aranha Livro 1 1 copy

Çan 1 copy

Сочинения в 3-Х томах 1 copy

Associated Works

Plato's Republic: Critical Essays (Critical Essays on the Classics Series) (1997) — Contributor — 35 copies

Tagged

Common Knowledge

- Legal name

- Murdoch, Dame Jean Iris

- Other names

- Murdoch, Jean Iris

- Birthdate

- 1919-07-15

- Date of death

- 1999-02-08

- Burial location

- Ashes scattered in the garden of Oxford Crematorium

- Gender

- female

- Nationality

- Ireland

- Birthplace

- Dublin, Ireland

- Place of death

- Oxfordshire, England, UK

- Cause of death

- Alzheimer's disease

- Places of residence

- Dublin, Ireland

London, England, UK

Oxford, Oxfordshire, England, UK - Education

- Oxford University (BA|1942|Somerville College)

University of Cambridge (Newnham College)

Badminton School, Bristol, Gloucestershire, England, UK - Occupations

- novelist

philosopher - Relationships

- Bayley, John (husband)

- Organizations

- American Academy of Arts and Letters (Foreign Honorary, Literature | 1975)

American Academy of Arts and Sciences (Foreign Honorary Member | 1982)

St Anne's College, Oxford University - Awards and honors

- Royal Society of Literature Companion of Literature

Order of the British Empire (Dame Commander ∙ 1987)

Golden PEN Award (1997)

James Tait Black Memorial Prize

Man Booker Prize - Agent

- Ed Victor

- Short biography

- Iris Murdoch was born in Dublin, Ireland, the only child of an Anglo-Irish family. When she was a baby, the family moved to London, where her father worked as a civil servant. She attended the Badminton School as a boarder from 1932 to 1938. In 1938, she enrolled at Oxford University, where she read Classics. She graduated with a First Class Honors degree in 1942 and got a job with the Treasury. In 1944, she joined the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), working in Brussels, Innsbruck, and Graz for two years. She then returned to her studies and became a postgraduate at Cambridge University. In 1948, she became a fellow of St Anne's College, Oxford, where she taught philosophy until 1963. In 1956, she married John Bayley, a literary critic, novelist, and English professor at Oxford. She published her debut novel, Under the Net, in 1954 and went on to produce 25 more novels and additional acclaimed works of philosophy, poetry and drama. She was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1982, and named a Dame Commander of Order of the British Empire in 1987. She was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in 1997 and died two years later.

Members

Discussions

Group Read, June 2022: The Sea, the Sea in 1001 Books to read before you die (July 2022)

Group Read, July 2018: Under The Net in 1001 Books to read before you die (July 2018)

The Bell in Iris Murdoch readers (February 2018)

Musing on Murdoch in General in Iris Murdoch readers (October 2017)

The Nice and the Good in Iris Murdoch readers (February 2017)

The Italian Girl in Iris Murdoch readers (November 2015)

The Sea, the Sea in Iris Murdoch readers (September 2015)

The Sandcastle in Iris Murdoch readers (January 2015)

The Green Knight in Iris Murdoch readers (May 2014)

The Unicorn in Iris Murdoch readers (February 2014)

***Group Read, October 2013: The Bell by Iris Murdoch in 1001 Books to read before you die (October 2013)

The Book and the Brotherhood in Iris Murdoch readers (October 2013)

A Severed Head in Iris Murdoch readers (May 2013)

The Black Prince in Iris Murdoch readers (May 2013)

The Philosopher's Pupil in Iris Murdoch readers (April 2013)

The Good Apprentice in Iris Murdoch readers (March 2013)

Something Special in Iris Murdoch readers (March 2013)

Henry and Cato in Iris Murdoch readers (February 2013)

A Word Child in Iris Murdoch readers (February 2013)

Bruno's Dream in Iris Murdoch readers (February 2013)

An Unofficial Rose in Iris Murdoch readers (February 2013)

Henry Cato in Iris Murdoch readers (January 2013)

Murdoch & Mayhem in 75 Books Challenge for 2012 (December 2012)

Reviews

Lists

Five star books (1)

Folio Society (1)

Unread books (1)

Revolutions (1)

First Novels (1)

Nifty Fifties (1)

Booker Prize (7)

1950s (1)

1970s (1)

Big Jubilee List (1)

Franklit (1)

5 Best 5 Years (1)

Read This Next (1)

Didactic Fiction (2)

Art of Reading (2)

Female Author (3)

A Novel Cure (1)

Favourite Books (1)

Summer Books (1)

Best Beach Reads (1)

Awards

You May Also Like

Associated Authors

Statistics

- Works

- 86

- Also by

- 10

- Members

- 26,178

- Popularity

- #799

- Rating

- 3.7

- Reviews

- 564

- ISBNs

- 692

- Languages

- 25

- Favorited

- 138

Iris Murdoch's debut novel is a disconcerting, shabby picaresque novel following the young hack writer Jake Donahue through a series of adventures. For the most part, it falls into my particular favourite type of picaresque: the adventure novel largely set over a few days. Murdoch is already comfortably inhabiting the body of a downtrodden, almost-broken, deeply strange protagonist, whose voice we can never entirely trust (Jake is keen to narrate his own story - a little too keen), and whose world seems to be a series of set-pieces that emerge out of otherwise ordinary life.

What is the plot? This is the kind of novel where certain literary snobs would say "the plot doesn't matter" but, reader, do not listen to them. In this case, the plot is precisely point. In a nutshell: Jake is kicked out by a woman, goes fawning back to two actress sisters from his past, uncovers a potential conspiracy involving a screenplay secretly adapted from a translation of a French novel he wrote some time ago, goes on a mad pub crawl with his gadabout mates, steals a film star dog who subsequently saves him from a police raid in the aftermath of a socialist party riot amidst an Ancient Roman film set in the middle of London, is mistaken for an escaped mental patient by an alley full of suburban gossips, pursues his lady love through Paris on Bastille Day, takes an unexpected job as a hospital orderly where his doubts and concerns come back to haunt him during a daring midnight visit to an incapacitated friend, and must consider whether he will position himself high(brow) or low on the unsteady rope ladder that is a literary career - or whether he even has the chops to climb the ladder at all. Throw in some Plato and a dash of Wittgenstein, a starling invasion straight out of Hitchcock's The Birds, and an avant-garde mime theatre, and you have Under the Net.

Murdoch's novel, first published in 1957, seems to sit quite comfortably within the (poorly named) 'Angry Young Man' cultural epoch - although Jake is not so much a victim of society as a personal exploration of those who exist comfortably in the margins. He has never held a job aside from writing until he signs up as an orderly, and is impressed by how easily he gets this one given how much his friends complain about the process. ("You will point out, and quite rightly", Jake says in one of Murdoch's moments of wry hilarity, that hospital orderly is perhaps a job where supply eclipses demand, "whereas what my friends were finding it so difficult to become was higher civil servants, columnists of the London dailies, officials of the British Council, fellows of colleges, or governors of the BBC. That is true.") Whereas her fellow novelists were interested in the temporal, Murdoch constantly allows us to see the metaphysical moments, the sublime and the ridiculous. But she is not writing, contrary to the philosophers who want to claim this text as their own, about what lies beyond the plot; Murdoch is finding the sublime within what is taking place, within human interaction and yearning.

And there is so much yearning. Although we have reason to doubt some of Jake's suspicions very early, he is a man easily compelled to new feeling: sudden love, sudden self-doubt, convinced he has destroyed a friendship or is under attack from the slightest of impulses. He is a fascinating character and, while I might concede that I'm not sure Murdoch entirely captures what it is like to be a male, the fulcrum around which her fairytale-like world rotates. (On a more terrestrial note, how times have changed - Jake tells us on the first page that his friend-cum-assistant Finn usually waits for him in bed, and later spends much of the book deeply pining for an old friend named Hugo. I had to separate myself entirely from 2020 to see these as the perfectly normal actions of a sensitive and impoverished heterosexual man!)

It is clear that one of my great projects for the 2020s will be to read all twenty-six of Murdoch's novels in order. I listened to the audiobook narrated by the pitch-perfect Samuel West, and I heartily recommend it for the way that West teases out both the uproarious comedy and the more delicate variety, yet I found myself returning to my copy of the book often to reread paragraphs or phrases just to let the author wash over me. I suspect that, structurally, or literarily, Under the Net is not one of Murdoch's greatest novels. (As her debut, it hardly could be!) But clearly from the Top 100 lists it frequently appears on, the novel has a place in the heart of many writers, and is perhaps an easier access point to her oeuvre than most.

Such fun.… (more)