Click on a thumbnail to go to Google Books.

|

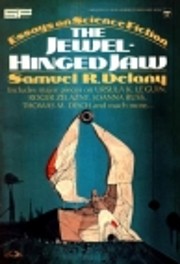

Loading... The Jewel-Hinged Jaw: Notes on the Language of Science Fiction (1977)by Samuel R. Delany

No current Talk conversations about this book. http://nhw.livejournal.com/521590.html This is a collection of a dozen pieces about sf, written between 1966 and 1976. They vary greatly in both length and quality; the longest, an article called "Shadows", is 80 pages, split into 60 sections which really appear just thrown together at random. I found some of this book stimulating but other bits overblown - for instance, Delany's apparently serious argument that there is no difference in average height between men and women, it's just that tall women and short men are oppressed by society and are in hiding as a result. I really bought the book for his essay on Thomas Disch (who I haven't read) and Roger Zelazny (who I have) and I thought that was well worth the cost. His longer piece on The Dispossessed had some sensible points in it but attacked the book for being insufficiently feminist and open-minded about sex, a view which will doubtless surprise many of its readers. So there we are; all interesting, but some bits much more interesting and worthwhile than others. no reviews | add a review

An indispensable work of science fiction criticism revised and expanded No library descriptions found. |

Current DiscussionsNonePopular covers

Google Books — Loading... Google Books — Loading...GenresMelvil Decimal System (DDC)814.54Literature English (North America) American essays 20th Century 1945-1999LC ClassificationRatingAverage: (4.14) (4.14)

Is this you?Become a LibraryThing Author. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

He does so by way of “reading protocols”, i.e. a certain (mostly implicit) set of rules and skills that is required to actually make sense of SFnal sentences. A phrase like (to quote one of his examples) “the door dilated”, used quite casually by Heinlein in one of his novels, just does not make any sense in a frame of reference that is not Science Fiction and that is not familiar with the concept of iris doors. Of course, one has to ask where this frame of reference comes from, as it needs to exist in some kind of contest; and when Delany finally describes Science Fiction as “What is possible” (as opposed to “what is” of realistic and “what is impossible” of fantastic fiction), he has moved away from strictly formal criteria back towards defining Sciene Fiction as a specific content again, as there is just no way to determine possibility without recourse to some kind of external, non-literary reality that would be independent of any specific form.

But then it is very doubtful whether Delany is interested in the merely formal anyway, for the essays collected in this volume also show him as someone with a keen interest not just in literary theory but also in politics, the politics of literature and even the politics of literary forms. This is at its most pronounced and its most detailed in his long essay on Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, which is in many ways the most remarkable and most important essay in this volume but also the one I had the most issues with. Most important because his examination of Le Guin’s work led Delany eventually to write his own novel Triton, most remarkable because it is such a close and fascinating reading, admiring even where it criticizes and raising many excellent points. But also the most problematic for the particular ad hominem argumentation of much of the criticism Delany levels against The Dispossessed – the homo in this case not being Le Guin but Delany himself, in so far as much of his argument consists simply of claiming that he has experienced things differently than Le Guin describes them and that therefore he must be right and the novel must be wrong.

Now, I agree that a depersonalized, absolutely objective point of view is at best an illusion, at worst an ideology that masks the most impoverished form of subjectivity, that the writing subject is always inextricably involved and engaged in any kind of debate and that therefore it is not automatically illegitimate to appeal to that subject’s experience. However, the simple referral to a subjective, individual experience does not constitute an argument - if it is not in some way mediated or refined through some degree of objectivity or generality, it remains a mere statement of opinion. And this is unfortunately where a large part of Delany’s essay on The Dispossessed remains stuck, a part that contrasts rather strangely with those bits where Delany’s criticism is solidly founded on a close reading of the novel’s text. The whole essay thus remains a somewhat uneven affair, but it is well worth reading – both for its insights on The Dispossessed and the snippets of Delany’s autobiography, as badly integrated as the two may be in this instance. I can’t help but suspect that Delany felt somewhat similarly, and that because of this, the essay might very well have been the starting point not just for Triton but for two of my favourite essays in this volume that explore precisely different ways of melding subjective experience with objective insight, the individual with the general.

The first one is the last piece in the collection, “A Fictional Architecture That Manages Only with Great Difficulty Not Once to Mention Harlan Ellison” - not really an essay, but a series of autobiographical sketches, a kaleidoscopic jumble of scenes where Science Fiction intersected with Delany’s life (or the other way round). As much as I enjoyed getting to Delany as a critic through the course of this volume, this final piece reminded that and why I like him most as a writer – it is dense, almost lyrical and dazzlingly brilliant and as far as I’m concerned, the high point of this collection. Also, you just have to love the title.

The second one is part of the appendix, the essay “Midcentury” which has as its subtitle “An Essay in Contextualization.” It undertakes an examination of the 1950s in the US by way of a parallel reading of some experiences from Delany’s youth and pictures from a contemporary exhibition, The Family of Man, showing both how young Delany’s preconceptions shaped his perceptions of the pictures, and how those in turn led to a certain shift in those very same preconceptions, and inscribing both into the context of their time. It is a brilliant and enlightening piece of work and I am a bit surprised that it was relegated to the appendix (which might have to do with the volume’s publishing history rather than with any perceived slightness of this and the other essay making up the appendix).

While The Jewel-Hinged Jaw is not Delany’s final word on Science Fiction and he apparently revised some of his views in later works, this still remains not only a groundbreaking collection, but also one that continues to excite and stimulate, with many thought-provoking essays not just on the theory of Science Fiction in general but also on individual authors (like Thomas M. Disch, Joanna Russ, Roger Zelazny) and works, as well as several particularly astringent observations on gender and race in the genre which sadly are almost as valid today as back in the seventies.