Baswood's books and music part 2

This is a continuation of the topic Baswood's books and music part 1 .

TalkClub Read 2016

Join LibraryThing to post.

This topic is currently marked as "dormant"—the last message is more than 90 days old. You can revive it by posting a reply.

1baswood

Time to open a new thread

Have been on holiday at Banyuls-sur-Mer: my favourite place on the French Mediterranean coast just above the Spanish border.

Rented an apartment on the beach with a great view from the terrace

Have been on holiday at Banyuls-sur-Mer: my favourite place on the French Mediterranean coast just above the Spanish border.

Rented an apartment on the beach with a great view from the terrace

2Caroline_McElwee

Perfect place to sit with your book and a glass of chilled wine!

5rebeccanyc

Ditto to all!

6FlorenceArt

Sounds like a great holiday! Hope you're not going to be too much impacted by not being a EU citizen in a couple of years.

7baswood

>6 FlorenceArt: Brexit - C'est pure folle.

At this moment in time I feel ashamed to be English. I am thinking of applying for French citizenship.

I am retired and so the impact on me financially will be small. I am angry at the loss of my EU citizenship.

Nightmare scenario is Boris Johnson leading the UK out of Europe and Donald Trump as president of the USA followed by Marie Le pen as president of France.

>2 Caroline_McElwee: perhaps I need to chill out with another glass of wine.

At this moment in time I feel ashamed to be English. I am thinking of applying for French citizenship.

I am retired and so the impact on me financially will be small. I am angry at the loss of my EU citizenship.

Nightmare scenario is Boris Johnson leading the UK out of Europe and Donald Trump as president of the USA followed by Marie Le pen as president of France.

>2 Caroline_McElwee: perhaps I need to chill out with another glass of wine.

8Caroline_McElwee

>7 baswood: I'm with you re BREXIT. I'm afraid if I try and drown my sorrows with booze I may still be going in ten years time...I'll put on the kettle.

9VivienneR

>7 baswood: My condolences. I too am an EU citizen and although it will only affect me in a minor way, I'm still upset at the referendum results but especially with Cameron.

Your scenario truly is a nightmare.

Your scenario truly is a nightmare.

10NanaCC

>7 baswood: your scenario scares the heck out of me. We keep saying Trump can't possibly win, but last August we were laughing that he actually was running and thought it was a big joke. Not laughing anymore.

12SassyLassy

My initial reaction, which has only been reenforced by subsequent events, was "cataclysmic". Less than a month ago I renewed my UK passport, with its EU cover and now that feeling of a greater world it always gave me is gone. Like Vivienne, living in Canada, it will have little effect on me in day to day life, but it is a real shock to the psyche nevertheless. Here's to Nicola Sturgeon and her efforts and to those of Alyn Smith.

>7 baswood: I was in the US the night of the vote, and stayed up to the bitter end watching the results. Bizarrely, the commentary on all the major news stations followed your nightmare scenario with Trump, adding to the completely surreal effect of the whole thing. Then there was Trump himself in Scotland the next day.

>7 baswood: I was in the US the night of the vote, and stayed up to the bitter end watching the results. Bizarrely, the commentary on all the major news stations followed your nightmare scenario with Trump, adding to the completely surreal effect of the whole thing. Then there was Trump himself in Scotland the next day.

14baswood

Dark Fire by C J Sansom

Sovereign by C J Sansom

Beach reading - well from the balcony overlooking the beach which was far more comfortable. Two books in the Mathew Shardlake crime series and both of them kept me up reading well into the night. Shardlake is a lawyer in 16th century England whose services are used by the power makers in the Tudor Court. In Dark Fire he is Thomas Cromwell’s man who is tasked with solving the mystery of the re-discovery of Greek Fire: a combustable material that could burn on water and which had been lost for centuries. Shardlake is soon the target for assassination attempts and with his assistant the streetwise Barak he must solve the mystery to save Cromwell’s skin. Sovereign finds Shardlake after the fall of Cromwell when he is tasked by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer to ensure the safe passage of the man Broderick, who has important information as one of the leaders of the Revolt of the North - the so called Pilgrimage of Grace. Shardlake must meet King Henry VIII progress at York and escort the prisoner back to London. Shardlake and Barak again find themselves in far deeper waters that they anticipate as this time the fate of Catherine Howard: Henry’s Queen, is also involved.

The world building, scene setting, historical reconstruction or whatever you like to call it is the main reason I have got hooked on this series. Sansom is careful not to stray too far from the known facts of the period and his murder mysteries enable him to bring his own interpretations to the characters that were the power brokers in Henry VIII court. The struggle between the catholic traditionalist and the protestant reformers who made up the factions containing the great families of the realm provide a stunning background to the stories. Shardlake was seen to be a reformer when working for Cromwell but with the rise of the Howard family at court following the execution of Ann Boleyn he must tread a more wary path when the traditionalists were gaining the upper hand. Sansom superbly captures the deadly intrigue surrounding the King and his coutiers in a world that was all too easily, likely to spill over into violence. Shardlake the crookbacked lawyer spends most of the books in fear of his life.

Dark Fire is set in London and there are thrilling descriptions of Shardlake riding on horseback through the streets of Cheapside, Fleet street, Ludgate, St Pauls, and Newgate. There are horrific descriptions of Newgate goal and the poorer areas around Thames Street, but it is the bustle, the crowds, the sense of a city bursting at the seams that fires the imagination. Shardlake seems to be constantly battling through the hubbub, pursuing or being pursued by mysterious forces intent on stopping his investigations. Sovereign is set largely in York, perhaps the second city of Tudor England, but a much poorer place compared to London. The city seems to be going backwards despite its collection of marvellous buildings. Both London and York are suffering the effects of the dissolution of the monasteries and while London seems to be embracing the change York as a city is suffering. What is clear however in both cities is that there is money to be made from the sale of land belonging to the church and those is favour with the King will benefit. A feature of Sovereign is the descriptions of the Kings Progress. In Tudor times it was still customary for the government led by the king to tour the kingdom usually during the summer months. In the great progress to York in 1541 Henry was intent on displaying his power, his government and all its followers was literally on the road cutting a huge swathe across the country and the purpose of the York progress was for Henry to receive oaths of allegiance from the great Northern families. The stately progress hampered by an appalling English summer and fraught with tension is brilliantly conveyed as is Shardlake’s return to London where he is arrested thrown in the Tower and suffers at the hands of the torturers.

Mathew Shardlake’s character has been set from the first novel in the series. His crookbacked deformity is mocked by many of the people with whom he has to deal, leading him to hide behind a gruff exterior. He is hard working and as honest as his predicaments allow him to be. He is trustworthy and together with his attention to detail and painstaking following through in his investigations makes him a useful tool to his paymasters, however it is these very characteristics that constantly get him into trouble. I was reading these two novels in conjunction with a history of the battle of Flodden 1513 and I had difficulty in telling apart the history from the historical novel.

Looking over the balcony at the people on the Mediterranean beach, relaxing, perhaps escaping from the drama and intrigues of their daily lives, there could hardly have been a greater contrast than with Mathew Shardlake’s desperate attempts to save himself and his friends from death or worse in Tudor England - 4 stars.

Sovereign by C J Sansom

Beach reading - well from the balcony overlooking the beach which was far more comfortable. Two books in the Mathew Shardlake crime series and both of them kept me up reading well into the night. Shardlake is a lawyer in 16th century England whose services are used by the power makers in the Tudor Court. In Dark Fire he is Thomas Cromwell’s man who is tasked with solving the mystery of the re-discovery of Greek Fire: a combustable material that could burn on water and which had been lost for centuries. Shardlake is soon the target for assassination attempts and with his assistant the streetwise Barak he must solve the mystery to save Cromwell’s skin. Sovereign finds Shardlake after the fall of Cromwell when he is tasked by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer to ensure the safe passage of the man Broderick, who has important information as one of the leaders of the Revolt of the North - the so called Pilgrimage of Grace. Shardlake must meet King Henry VIII progress at York and escort the prisoner back to London. Shardlake and Barak again find themselves in far deeper waters that they anticipate as this time the fate of Catherine Howard: Henry’s Queen, is also involved.

The world building, scene setting, historical reconstruction or whatever you like to call it is the main reason I have got hooked on this series. Sansom is careful not to stray too far from the known facts of the period and his murder mysteries enable him to bring his own interpretations to the characters that were the power brokers in Henry VIII court. The struggle between the catholic traditionalist and the protestant reformers who made up the factions containing the great families of the realm provide a stunning background to the stories. Shardlake was seen to be a reformer when working for Cromwell but with the rise of the Howard family at court following the execution of Ann Boleyn he must tread a more wary path when the traditionalists were gaining the upper hand. Sansom superbly captures the deadly intrigue surrounding the King and his coutiers in a world that was all too easily, likely to spill over into violence. Shardlake the crookbacked lawyer spends most of the books in fear of his life.

Dark Fire is set in London and there are thrilling descriptions of Shardlake riding on horseback through the streets of Cheapside, Fleet street, Ludgate, St Pauls, and Newgate. There are horrific descriptions of Newgate goal and the poorer areas around Thames Street, but it is the bustle, the crowds, the sense of a city bursting at the seams that fires the imagination. Shardlake seems to be constantly battling through the hubbub, pursuing or being pursued by mysterious forces intent on stopping his investigations. Sovereign is set largely in York, perhaps the second city of Tudor England, but a much poorer place compared to London. The city seems to be going backwards despite its collection of marvellous buildings. Both London and York are suffering the effects of the dissolution of the monasteries and while London seems to be embracing the change York as a city is suffering. What is clear however in both cities is that there is money to be made from the sale of land belonging to the church and those is favour with the King will benefit. A feature of Sovereign is the descriptions of the Kings Progress. In Tudor times it was still customary for the government led by the king to tour the kingdom usually during the summer months. In the great progress to York in 1541 Henry was intent on displaying his power, his government and all its followers was literally on the road cutting a huge swathe across the country and the purpose of the York progress was for Henry to receive oaths of allegiance from the great Northern families. The stately progress hampered by an appalling English summer and fraught with tension is brilliantly conveyed as is Shardlake’s return to London where he is arrested thrown in the Tower and suffers at the hands of the torturers.

Mathew Shardlake’s character has been set from the first novel in the series. His crookbacked deformity is mocked by many of the people with whom he has to deal, leading him to hide behind a gruff exterior. He is hard working and as honest as his predicaments allow him to be. He is trustworthy and together with his attention to detail and painstaking following through in his investigations makes him a useful tool to his paymasters, however it is these very characteristics that constantly get him into trouble. I was reading these two novels in conjunction with a history of the battle of Flodden 1513 and I had difficulty in telling apart the history from the historical novel.

Looking over the balcony at the people on the Mediterranean beach, relaxing, perhaps escaping from the drama and intrigues of their daily lives, there could hardly have been a greater contrast than with Mathew Shardlake’s desperate attempts to save himself and his friends from death or worse in Tudor England - 4 stars.

16baswood

Fatal Rivalry: Flodden 1513 by George Goodwin.

A very readable slice of history which is subtitled Henry VIII, James IV and the battle for Renaissance Britain. Goodwin has the idea of comparing and contrasting the two kings in an age when ideas from the Italian renaissance had seeped into the culture of both England and Scotland.

Goodwin rolls back the period to 1496 when Henry VII was on the throne in England and James IV had established himself as king of Scotland. James had given refuge to Perkin Warbeck a Yorkist pretender to the English throne and it was a time of tit for tat raids across the Border. Warbeck was never able to mount a serious challenge and James did little more than provide him a refuge and lend him a ship. Warwick was eventually captured and hanged at Tyburn in 1499. Meanwhile Henry VII was negotiating with James IV a treaty of perpetual peace which was finally signed in 1503. From then until its breakdown in 1513 the treaty held and Goodwin fills in the details of James IV achievements in uniting the Scottish clans and making himself their undisputed king. He also tells the background history of the major players on the continent: France, the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope and how they influenced the two kingdoms on the British Isles.

When Henry VIII came to the English throne in 1509 he had a lot of catching up to do to surpass the renaissance court of James IV. In his younger days he saw himself as a warrior king and it was not long before he was planning an invasion of France and was sparking off an arms race in ship building. The irony of comparing the two kings was that when the battle of Flodden was fought Henry was in France leading an invasion force, while James IV was leading his country on the battlefield in Northern England. Henry had left the control of the government in the capable hands of his first wife Catherine of Aragon and it was she who organised the war effort against the Scots. Her commander in the field was Thomas Howard earl of Surrey who was smarting at not being with the king in France. The traditional catholic Howard family were being eclipsed in the Tudor court and Thomas Howard and his son also Thomas Howard (referred to as the admiral in the text) were desperate to prove themselves. They had to win against the Scots to secure their family in England.

Goodwins background to the battle is impressive taking up nearly two thirds of his book and when the war eventually comes he does an equally excellent job in the lead up to Flodden and then describing the battle itself. The opposing armies were fairly equally matched and James started off with many advantages in that he had prepared his position well and had at his disposal (so he thought) the more effective artillery. Goodwin does an excellent job in describing why he came unstuck and his previous background history goes a long way in backing up his arguments.

The book has plenty of notes a good bibliography and index. It also contains an interesting chapter on a select list of Flodden related organisations and places to visit, all of which points to the book being aimed at the more general reader. I am not tempted to visit the battlefield or become involved in the Flodden Archeological 500 project, but its kinda nice know they are their. A very enjoyable read and a four star history

A very readable slice of history which is subtitled Henry VIII, James IV and the battle for Renaissance Britain. Goodwin has the idea of comparing and contrasting the two kings in an age when ideas from the Italian renaissance had seeped into the culture of both England and Scotland.

Goodwin rolls back the period to 1496 when Henry VII was on the throne in England and James IV had established himself as king of Scotland. James had given refuge to Perkin Warbeck a Yorkist pretender to the English throne and it was a time of tit for tat raids across the Border. Warbeck was never able to mount a serious challenge and James did little more than provide him a refuge and lend him a ship. Warwick was eventually captured and hanged at Tyburn in 1499. Meanwhile Henry VII was negotiating with James IV a treaty of perpetual peace which was finally signed in 1503. From then until its breakdown in 1513 the treaty held and Goodwin fills in the details of James IV achievements in uniting the Scottish clans and making himself their undisputed king. He also tells the background history of the major players on the continent: France, the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope and how they influenced the two kingdoms on the British Isles.

When Henry VIII came to the English throne in 1509 he had a lot of catching up to do to surpass the renaissance court of James IV. In his younger days he saw himself as a warrior king and it was not long before he was planning an invasion of France and was sparking off an arms race in ship building. The irony of comparing the two kings was that when the battle of Flodden was fought Henry was in France leading an invasion force, while James IV was leading his country on the battlefield in Northern England. Henry had left the control of the government in the capable hands of his first wife Catherine of Aragon and it was she who organised the war effort against the Scots. Her commander in the field was Thomas Howard earl of Surrey who was smarting at not being with the king in France. The traditional catholic Howard family were being eclipsed in the Tudor court and Thomas Howard and his son also Thomas Howard (referred to as the admiral in the text) were desperate to prove themselves. They had to win against the Scots to secure their family in England.

Goodwins background to the battle is impressive taking up nearly two thirds of his book and when the war eventually comes he does an equally excellent job in the lead up to Flodden and then describing the battle itself. The opposing armies were fairly equally matched and James started off with many advantages in that he had prepared his position well and had at his disposal (so he thought) the more effective artillery. Goodwin does an excellent job in describing why he came unstuck and his previous background history goes a long way in backing up his arguments.

The book has plenty of notes a good bibliography and index. It also contains an interesting chapter on a select list of Flodden related organisations and places to visit, all of which points to the book being aimed at the more general reader. I am not tempted to visit the battlefield or become involved in the Flodden Archeological 500 project, but its kinda nice know they are their. A very enjoyable read and a four star history

17dchaikin

Enjoyed these, Bas. I think just your reviews had me in a state of anticipation. The books must be fun. Shardlake comes up a lot here (or should I say Sansom). I find it hard to believe a mystery set in that era could work, but reviews are always so positive.

18FlorenceArt

>13 baswood: Wonderful photo!

Like Dan, I'm rather skeptical toward medieval mysteries (or is that Renaissance in this case?), but these sound worth checking out. Maybe, some day.

Like Dan, I'm rather skeptical toward medieval mysteries (or is that Renaissance in this case?), but these sound worth checking out. Maybe, some day.

19SassyLassy

>16 baswood: This is on my TBR pile, and since I seem to be reading far too much fiction (when I actually read), you have convinced me to move it up.

I love the idea of reading Sansom in that beautiful spot. Somehow, the contrast works to make the fictional situation more real.

I love the idea of reading Sansom in that beautiful spot. Somehow, the contrast works to make the fictional situation more real.

20sibylline

Super reviews! I galloped through Sansom last winter and hugely enjoyed them and the history review it triggered. I've discovered I like historical mysteries even though, generally, I'm not keen on historical fiction (with some huge exceptions).

23baswood

The Meursault Investigation by Kamel Daoud

Children of the New world; A novel of the Algerian war by Assia Djebar

The Algerian war of Independence 1954-62 was fought between France and the independence movement in Algeria. It was a conflict characterised by guerrilla warfare and was notorious for the weapon of torture used by both sides. It was a bitter and complex struggle between a colonial power and its former colony with terror attacks and retribution being key elements. The Meursault Investigation and Children of the New World are novels written by Algerian authors whose central themes radiate from events during the war. One is clever, witty, utterly modern and ultimately vacuous, the other is a profound exploration of Muslim men and women caught in a dirty war and fighting for survival.

The Meursault Investigation is in part a reworking of Albert Camus famous novel L’estranger in which an unnamed Arab is killed on the beach by the Frenchman Meursault. Kamel Daoud gives the Arab a name: Musa, thereby providing a critique of Camus’ colonial perspective in centring his story on the Frenchman: Daoud imagines that Musa’s younger brother and his mother painstakingly investigate the murder; an event that shapes the rest of their lives. It is the mother who is the prime mover cajoling her surviving son into greater efforts to attain some sort of closure that ends with him taking out his own retribution.

Daoud’s novel starts with the single sentence: “Mother’s still alive” today which mirrors the first sentence in Camus’ novel: “Mother died today” and from the moment I read this I was alert to the idea that this was a novel too clever for its own good; nothing I read subsequently changed my view. Daoud’s writing imitates Camus short staccato-like sentence structure and is alive with references to Camus’ novel and other writings. For those readers who are not familiar with Camus novel Daoud must outline the story and he does it like this:

“I’m going to outline the story before I tell it to you. A man who knows how to write kills an Arab who, on the day he dies, doesn’t even have a name, as if he had hung it on a nail somewhere before stepping onto the stage. Then the man begins to explain that his act was the fault of a God that doesn’t exist and that he did it because of what he’d just realised in the sun and because the sea salt obliged him to shut his eyes……..”

This was the moment I threw the book across the room for two reasons. Daoud by a sleight of hand is making the reader believe that Camus’ novel was a real life testimony - “A man who knows how to write kills an Arab” This is a lie. Although Camus’ novel was written in the first person, the point of view was of his hero Meursault not his own. This is important because Camus has been castigated as a colonialist and this book is riding on a wave that furthers that myth. Camus was a Frenchman born and raised in Algiers who could not bring himself to support the independence movement because of the horrors of the war and fears for his family. Unlike other armchair critics on the left (Sartre et al) and at some personal risk to himself, he went to Algeria near the start of hostilities and attempted to broker a peace. He had a history of sympathy and support for the Arabs from his days as a journalist and so does not deserve the acrimony he has since garnered. The other reason for tossing Daoud’s book is the crude attempt to belittle Camus writing, which I think is evident from the extract above.

How refreshing then to turn to Assia Djebar to find a novelist who effortlessly tunes into the lives of both Arab and French Algerians at a time near the start of hostilities. She does not need the crutch of a famous novel of the past on which to base her story, but weaves her themes into a single day in the actions of eight characters whose lives intersect on a day when everything changes for each of them. Her characters get a chapter each starting with Cherifa’s story, She is a muslim women whose respect for tradition and family keep her bound within the confines of her own house. From her courtyard along with other women of surrounding dwellings she watches the fighting taking place over the mountain that dominates the small town.

“The days of intense fighting pass quickly inside the homes that people think of as unseeing, but that now gape at the war, which is masked as a gigantic game etched out in space. The planes are soaring and diving black spots that leave white trails, ephemeral arabesques that seem to be drawn by chance, like a mysterious but lethal script . “Oh God” a woman cries when one of them nose dives into flames and the bullets that they can picture in their mind, but then it shoots up out of the smoke running along the ground (“Death the damned thing has brought death in its wake!”) There it is again, spiralling way up in the sky; then nearby artillery fire ruptures the air, so close that the walls shake”

The women are fascinated by the aerial ballet, but are not just interested bystanders; Cherifa’s mother-in-law has recently been killed in the courtyard by falling shrapnel.

Each chapter fills in a little of the back story to the characters and so we learn that this is Cherifa’s second marriage; she is married to Youssef and is very much in love with him and fears for his safety being aware that he is a local political leader and so is in danger of his life. Her story also introduces many of the other characters, who will have a chapter to themselves, but Cherifa’s own heroic walk across town (she has rarely ventured out of her house and certainly not alone) to warn her husband of impending arrest is told in another characters chapter and so Djebar skilfully interlinks her chapters to give a mosaic affect to her story.

The first four chapters tell the women’s story; Lila is fresh from university somewhat westernised and married to her college sweetheart who has left her to fight with the rebels in the mountains, then there is Salima a teacher at the local girls school who is arrested and interrogated and finally Touma who has become an informer for the French police. There are four chapters that fill in the male’s stories, but still it is the women’s stories that take priority, many of the characters are related or know each other from living in the small town, which is changing rapidly due to the internecine conflicts which overtake their lives. The book has a clear female perspective and it is their pain, horror, and fear that we, the readers are made to feel, however Djebar never loses sight of other aspects of their characters and their strength, courage and love predominate for the most part. The female characters generally have a deep understanding of their male counterparts and live their lives accordingly, but are not afraid to stand their ground in a society that is male dominated and they bring a sensuousness to their relationships that they are not afraid to express.

Two novelists then that take a very different approach and while it could be argued that Daoud’s book is not wholly concerned with the war, as its other main theme is Camus’ existentialist viewpoint, however it does increasingly move towards the conflict in Algeria when it runs out of things to say about Camus. I was pleased to have read (yes I did pick it up from the floor) Daoud’s book first, because once I got into Djebar’s book I understood how superficial Daoud was. Reading the Meursault Investigation was like listening to politicians campaigning for Britain to leave the European Union; much cleverness and bluster on the surface, but underneath no substance and what was even worse a lack of honesty. Yes of course Daoud’s book has been nominated and won literary prizes but the gloss did not fool this reader. If you haven’t read Camus’ L’étranger read that and don't bother with The Meursault Investigation unless you are in the mood for a quick and painless beach read. Assia Djebar’s book is the real deal, its beautifully written and well translated from the French and has an authenticity to it that comes from the authors deep empathy with her characters and the situation in her country of birth.

The Meursault Investigation - 2 stars

Children of the New World - 4.5 stars.

Children of the New world; A novel of the Algerian war by Assia Djebar

The Algerian war of Independence 1954-62 was fought between France and the independence movement in Algeria. It was a conflict characterised by guerrilla warfare and was notorious for the weapon of torture used by both sides. It was a bitter and complex struggle between a colonial power and its former colony with terror attacks and retribution being key elements. The Meursault Investigation and Children of the New World are novels written by Algerian authors whose central themes radiate from events during the war. One is clever, witty, utterly modern and ultimately vacuous, the other is a profound exploration of Muslim men and women caught in a dirty war and fighting for survival.

The Meursault Investigation is in part a reworking of Albert Camus famous novel L’estranger in which an unnamed Arab is killed on the beach by the Frenchman Meursault. Kamel Daoud gives the Arab a name: Musa, thereby providing a critique of Camus’ colonial perspective in centring his story on the Frenchman: Daoud imagines that Musa’s younger brother and his mother painstakingly investigate the murder; an event that shapes the rest of their lives. It is the mother who is the prime mover cajoling her surviving son into greater efforts to attain some sort of closure that ends with him taking out his own retribution.

Daoud’s novel starts with the single sentence: “Mother’s still alive” today which mirrors the first sentence in Camus’ novel: “Mother died today” and from the moment I read this I was alert to the idea that this was a novel too clever for its own good; nothing I read subsequently changed my view. Daoud’s writing imitates Camus short staccato-like sentence structure and is alive with references to Camus’ novel and other writings. For those readers who are not familiar with Camus novel Daoud must outline the story and he does it like this:

“I’m going to outline the story before I tell it to you. A man who knows how to write kills an Arab who, on the day he dies, doesn’t even have a name, as if he had hung it on a nail somewhere before stepping onto the stage. Then the man begins to explain that his act was the fault of a God that doesn’t exist and that he did it because of what he’d just realised in the sun and because the sea salt obliged him to shut his eyes……..”

This was the moment I threw the book across the room for two reasons. Daoud by a sleight of hand is making the reader believe that Camus’ novel was a real life testimony - “A man who knows how to write kills an Arab” This is a lie. Although Camus’ novel was written in the first person, the point of view was of his hero Meursault not his own. This is important because Camus has been castigated as a colonialist and this book is riding on a wave that furthers that myth. Camus was a Frenchman born and raised in Algiers who could not bring himself to support the independence movement because of the horrors of the war and fears for his family. Unlike other armchair critics on the left (Sartre et al) and at some personal risk to himself, he went to Algeria near the start of hostilities and attempted to broker a peace. He had a history of sympathy and support for the Arabs from his days as a journalist and so does not deserve the acrimony he has since garnered. The other reason for tossing Daoud’s book is the crude attempt to belittle Camus writing, which I think is evident from the extract above.

How refreshing then to turn to Assia Djebar to find a novelist who effortlessly tunes into the lives of both Arab and French Algerians at a time near the start of hostilities. She does not need the crutch of a famous novel of the past on which to base her story, but weaves her themes into a single day in the actions of eight characters whose lives intersect on a day when everything changes for each of them. Her characters get a chapter each starting with Cherifa’s story, She is a muslim women whose respect for tradition and family keep her bound within the confines of her own house. From her courtyard along with other women of surrounding dwellings she watches the fighting taking place over the mountain that dominates the small town.

“The days of intense fighting pass quickly inside the homes that people think of as unseeing, but that now gape at the war, which is masked as a gigantic game etched out in space. The planes are soaring and diving black spots that leave white trails, ephemeral arabesques that seem to be drawn by chance, like a mysterious but lethal script . “Oh God” a woman cries when one of them nose dives into flames and the bullets that they can picture in their mind, but then it shoots up out of the smoke running along the ground (“Death the damned thing has brought death in its wake!”) There it is again, spiralling way up in the sky; then nearby artillery fire ruptures the air, so close that the walls shake”

The women are fascinated by the aerial ballet, but are not just interested bystanders; Cherifa’s mother-in-law has recently been killed in the courtyard by falling shrapnel.

Each chapter fills in a little of the back story to the characters and so we learn that this is Cherifa’s second marriage; she is married to Youssef and is very much in love with him and fears for his safety being aware that he is a local political leader and so is in danger of his life. Her story also introduces many of the other characters, who will have a chapter to themselves, but Cherifa’s own heroic walk across town (she has rarely ventured out of her house and certainly not alone) to warn her husband of impending arrest is told in another characters chapter and so Djebar skilfully interlinks her chapters to give a mosaic affect to her story.

The first four chapters tell the women’s story; Lila is fresh from university somewhat westernised and married to her college sweetheart who has left her to fight with the rebels in the mountains, then there is Salima a teacher at the local girls school who is arrested and interrogated and finally Touma who has become an informer for the French police. There are four chapters that fill in the male’s stories, but still it is the women’s stories that take priority, many of the characters are related or know each other from living in the small town, which is changing rapidly due to the internecine conflicts which overtake their lives. The book has a clear female perspective and it is their pain, horror, and fear that we, the readers are made to feel, however Djebar never loses sight of other aspects of their characters and their strength, courage and love predominate for the most part. The female characters generally have a deep understanding of their male counterparts and live their lives accordingly, but are not afraid to stand their ground in a society that is male dominated and they bring a sensuousness to their relationships that they are not afraid to express.

Two novelists then that take a very different approach and while it could be argued that Daoud’s book is not wholly concerned with the war, as its other main theme is Camus’ existentialist viewpoint, however it does increasingly move towards the conflict in Algeria when it runs out of things to say about Camus. I was pleased to have read (yes I did pick it up from the floor) Daoud’s book first, because once I got into Djebar’s book I understood how superficial Daoud was. Reading the Meursault Investigation was like listening to politicians campaigning for Britain to leave the European Union; much cleverness and bluster on the surface, but underneath no substance and what was even worse a lack of honesty. Yes of course Daoud’s book has been nominated and won literary prizes but the gloss did not fool this reader. If you haven’t read Camus’ L’étranger read that and don't bother with The Meursault Investigation unless you are in the mood for a quick and painless beach read. Assia Djebar’s book is the real deal, its beautifully written and well translated from the French and has an authenticity to it that comes from the authors deep empathy with her characters and the situation in her country of birth.

The Meursault Investigation - 2 stars

Children of the New World - 4.5 stars.

24SassyLassy

Fascinating reviews and comparison of the two novels, well maybe 2+ novels for the added Camus. Loved the analogy of those campaigning politicians.

25mabith

Love the side by side reviews of the Algerian novels. Major book bullet for Children of the New World.

26thorold

>23 baswood: Interesting. The English reviews I've seen of Daoud's book were all very positive, but I did a quick Google and saw that the French ones are a bit more mixed. This one: http://salon-litteraire.com/fr/kamel-daoud/review/1909673-kamel-daoud-meursault-... comes to a rather similar conclusion to yours (that Daoud is wrong-headedly mixing up Camus with Meursault) and says that it's not so much a spin-off as a rip-off. But there are also a couple of others who seem to think that Daoud is a genius who should have got the Goncourt instead of Pas pleurer.

27dchaikin

Enjoyed your post and the comparison of these books. Daoud was clearly using Camus not as immitation, but as a dialogue. Too bad it didn't work, and it doesn't sound pleasant. Great encouragement to read Djebar.

28janeajones

Wonderfully pointed reviews.

29baswood

>26 thorold: it's not so much a spin-off as a rip-off. yes I like that.

30AlisonY

Such an interesting review. I had no idea of the back story about Camus either - fascinating stuff.

31Caroline_McElwee

I think you must be having a long snooze in a hammock!

>23 baswood: I do have this, but heard it was helpful to have reread The Outsider. Not sure I will get to either for some while.

>23 baswood: I do have this, but heard it was helpful to have reread The Outsider. Not sure I will get to either for some while.

32baswood

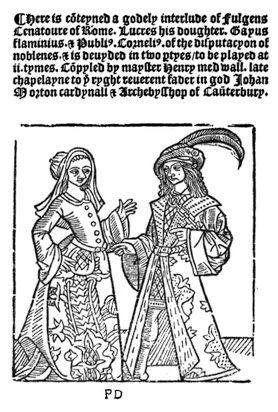

The poems of Henry Howard Earl of Surrey, Frederick Morgan Padelford

Henry Howard (1517-1547) was executed during the very last days of the reign of Henry VIII. Born of noble blood his short but eventful life as a courtier, soldier, roustabout was combined with claims for him to be the most important English poet since the days of Chaucer. In Tottel’s Miscellany (published 1557) which was the first ever printed anthology of English verse Henry Howard was given pride of place and almost all of the poems attributed to him were published in that volume. During his lifetime his poems would have been circulated amongst friends and courtiers and what a life it was.

Imprisoned at least three times, once in Windsor Castle for smacking a fellow courtier in the grounds of the Kings Palace, once in Fleet Prison London for eating meat during lent and smashing windows with a stone bow in the more well-to-do districts of London and finally in the Tower of London on a charge of high treason. In an age of hot blooded courtiers he seemed to be more hot bloodied than most and that along with his pride of his noble blood and his name made him a target at court. Henry Howard Earl of Surrey was probably a catholic in an age of reformation. The Howard family were continually at odds with the more protestant Seymours and the changing face of fortune at King Henry VIII’s court was not something that a man like Henry Howard found it easy to negotiate. As a youth he was chosen to be a companion to Henry VIII’s bastard son the Duke of Richmond and so had pride of place at court. The Duke of Richmond died in his late teens and Henry Howard’s next career was as a soldier supporting his father the Duke of Norfolk who was engaged in putting down the great northern rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. After his spell in prison for his window smashing exploits Henry VIII sent him to France as head of a 5000 strong advance force intent on invasion. After leading an ill fated sortie outside of Boulogne he was replaced by one of the Seymour family and returned to England and it wasn’t long before intrigues at court led to him being imprisoned in the Tower on a charge of high treason.

It is fortunate I suppose that his time in prison allowed him to concentrate on his poetry and Padelford points to three reasons why he should be considered as one of greats in the early canon. Firstly it was his insistence that the metrical accent should fall upon words which are naturally stressed because of their importance, and upon the accented, rather than the unaccented syllables of such words. This went against the grain of much poetry at the time and because of the development of the English language during Tudor times, making it much more recognisable to modern readers than the language of Chaucer (a century and a half earlier) it makes it easier to understand. The second reason was his establishment of the sonnet form known as the English sonnet whose rhyming scheme abab, cded, efef, gg would be taken to such great heights by Shakespeare half a century later. He has also been credited with the introduction of blank verse through his translations of the Æneid. Thirdly his use of alliteration and his experimentation with other verse forms set a pattern for other poets to follow.

So what is the modern reader to make of the forty or so original poems by Henry Howard in existence today. Firstly some of the more famous sonnets are not really original being loose translations either of Petrarch’s Italian renaissance poetry or taken from classical authors. However it was Howards adaption into the English sonnet form and his addition of more personal and imaginative lines and phrases that make them so very readable today: Here is an example from poemhunter on the internet:

Alas! so all things now do hold their peace,

Heaven and earth disturbed in nothing.

The beasts, the air, the birds their song do cease,

The night{:e}s chare the stars about doth bring.

Calm is the sea, the waves work less and less:

So am not I, whom love, alas, doth wring,

Bringing before my face the great increase

Of my desires, whereat I weep and sing

In joy and woe, as in a doubtful ease.

For my sweet thoughts sometime do pleasure bring,

But by and by the cause of my disease

Gives me a pang that inwardly doth sting,

When that I think what grief it is again

To live and lack the thing should rid my pain.

This was adapted from a poem by Petrarch and shows Howards willingness to adapt the rhyming scheme to fit his needs.

Howards range of poetry was quite astonishing. There are love poems, autobiographical poems, moral and didactic poems, elegiac poems, tributes to other poets and of course his translations. There are sonnets, six line stanzas, tetrameter quatrains with alternate rhymes and a real product of his times Poulters measure. Poulters measure is an iambic couplet of 12 and 14 syllable lines that produces a curious sing song effect and has long since gone out of fashion.

Here is an extended sonnet written by Henry Howard written in the Tower of London when facing death following his trial for treason. He faces death with courage and remembrance of a life with no regret, but he is also at pains to express his disdain on the cowardly courtiers that have triumphed over him and his family.

THE STORMS are past; the clouds are overblown;

And humble chere great rigour hath represt.

For the default is set a pain foreknown;

And patience graft in a determined breast.

And in the heart, where heaps of griefs were grown,

The sweet revenge hath planted mirth and rest.

No company so pleasant as mine own.

. . . . . . . .

Thraldom at large hath made this prison free.

Danger well past, remembered, works delight.

Of ling’ring doubts such hope is sprung, pardie!

That nought I find displeasant in my sight,

But when my glass presented unto me

The cureless wound that bleedeth day and night.

To think, alas! such hap should granted be

Unto a wretch, that hath no heart to fight,

To spill that blood, that hath so oft been shed,

For Britain’s sake, alas! and now is dead!

And so we find Henry Howard belligerent to the end. He may well have been pumped up with pride and ruthless in his pursuit of power and influence, but he was no different from others at the court of Henry VIII. Perhaps Henry Howard lacked the subtlety to survive such a bear pit; he refers to himself in one of his poems as a man of war and in another who lives

“The rakehell life that longs to loves disported”

I found his writing for the most part clear and direct with much interest for the modern reader with an interest in Tudor times. Padelfords book which is free on the internet at archive.org contains as much as you might want to know. For me a five star read.

Henry Howard (1517-1547) was executed during the very last days of the reign of Henry VIII. Born of noble blood his short but eventful life as a courtier, soldier, roustabout was combined with claims for him to be the most important English poet since the days of Chaucer. In Tottel’s Miscellany (published 1557) which was the first ever printed anthology of English verse Henry Howard was given pride of place and almost all of the poems attributed to him were published in that volume. During his lifetime his poems would have been circulated amongst friends and courtiers and what a life it was.

Imprisoned at least three times, once in Windsor Castle for smacking a fellow courtier in the grounds of the Kings Palace, once in Fleet Prison London for eating meat during lent and smashing windows with a stone bow in the more well-to-do districts of London and finally in the Tower of London on a charge of high treason. In an age of hot blooded courtiers he seemed to be more hot bloodied than most and that along with his pride of his noble blood and his name made him a target at court. Henry Howard Earl of Surrey was probably a catholic in an age of reformation. The Howard family were continually at odds with the more protestant Seymours and the changing face of fortune at King Henry VIII’s court was not something that a man like Henry Howard found it easy to negotiate. As a youth he was chosen to be a companion to Henry VIII’s bastard son the Duke of Richmond and so had pride of place at court. The Duke of Richmond died in his late teens and Henry Howard’s next career was as a soldier supporting his father the Duke of Norfolk who was engaged in putting down the great northern rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. After his spell in prison for his window smashing exploits Henry VIII sent him to France as head of a 5000 strong advance force intent on invasion. After leading an ill fated sortie outside of Boulogne he was replaced by one of the Seymour family and returned to England and it wasn’t long before intrigues at court led to him being imprisoned in the Tower on a charge of high treason.

It is fortunate I suppose that his time in prison allowed him to concentrate on his poetry and Padelford points to three reasons why he should be considered as one of greats in the early canon. Firstly it was his insistence that the metrical accent should fall upon words which are naturally stressed because of their importance, and upon the accented, rather than the unaccented syllables of such words. This went against the grain of much poetry at the time and because of the development of the English language during Tudor times, making it much more recognisable to modern readers than the language of Chaucer (a century and a half earlier) it makes it easier to understand. The second reason was his establishment of the sonnet form known as the English sonnet whose rhyming scheme abab, cded, efef, gg would be taken to such great heights by Shakespeare half a century later. He has also been credited with the introduction of blank verse through his translations of the Æneid. Thirdly his use of alliteration and his experimentation with other verse forms set a pattern for other poets to follow.

So what is the modern reader to make of the forty or so original poems by Henry Howard in existence today. Firstly some of the more famous sonnets are not really original being loose translations either of Petrarch’s Italian renaissance poetry or taken from classical authors. However it was Howards adaption into the English sonnet form and his addition of more personal and imaginative lines and phrases that make them so very readable today: Here is an example from poemhunter on the internet:

Alas! so all things now do hold their peace,

Heaven and earth disturbed in nothing.

The beasts, the air, the birds their song do cease,

The night{:e}s chare the stars about doth bring.

Calm is the sea, the waves work less and less:

So am not I, whom love, alas, doth wring,

Bringing before my face the great increase

Of my desires, whereat I weep and sing

In joy and woe, as in a doubtful ease.

For my sweet thoughts sometime do pleasure bring,

But by and by the cause of my disease

Gives me a pang that inwardly doth sting,

When that I think what grief it is again

To live and lack the thing should rid my pain.

This was adapted from a poem by Petrarch and shows Howards willingness to adapt the rhyming scheme to fit his needs.

Howards range of poetry was quite astonishing. There are love poems, autobiographical poems, moral and didactic poems, elegiac poems, tributes to other poets and of course his translations. There are sonnets, six line stanzas, tetrameter quatrains with alternate rhymes and a real product of his times Poulters measure. Poulters measure is an iambic couplet of 12 and 14 syllable lines that produces a curious sing song effect and has long since gone out of fashion.

Here is an extended sonnet written by Henry Howard written in the Tower of London when facing death following his trial for treason. He faces death with courage and remembrance of a life with no regret, but he is also at pains to express his disdain on the cowardly courtiers that have triumphed over him and his family.

THE STORMS are past; the clouds are overblown;

And humble chere great rigour hath represt.

For the default is set a pain foreknown;

And patience graft in a determined breast.

And in the heart, where heaps of griefs were grown,

The sweet revenge hath planted mirth and rest.

No company so pleasant as mine own.

. . . . . . . .

Thraldom at large hath made this prison free.

Danger well past, remembered, works delight.

Of ling’ring doubts such hope is sprung, pardie!

That nought I find displeasant in my sight,

But when my glass presented unto me

The cureless wound that bleedeth day and night.

To think, alas! such hap should granted be

Unto a wretch, that hath no heart to fight,

To spill that blood, that hath so oft been shed,

For Britain’s sake, alas! and now is dead!

And so we find Henry Howard belligerent to the end. He may well have been pumped up with pride and ruthless in his pursuit of power and influence, but he was no different from others at the court of Henry VIII. Perhaps Henry Howard lacked the subtlety to survive such a bear pit; he refers to himself in one of his poems as a man of war and in another who lives

“The rakehell life that longs to loves disported”

I found his writing for the most part clear and direct with much interest for the modern reader with an interest in Tudor times. Padelfords book which is free on the internet at archive.org contains as much as you might want to know. For me a five star read.

33dchaikin

I've never heard of Henry Howard. Very interesting life story and poetic story. Enjoyed your review.

35baswood

Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind,

But as for me, hélas, I may no more.

The vain travail hath wearied me so sore,

I am of them that farthest cometh behind.

Yet may I by no means my wearied mind

Draw from the deer, but as she fleeth afore

Fainting I follow. I leave off therefore,

Sithens in a net I seek to hold the wind.

Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt,

As well as I may spend his time in vain.

And graven with diamonds in letters plain

There is written, her fair neck round about:

Noli me tangere, for Caesar's I am,

And wild for to hold, though I seem tame.

Thomas Wyatt

It is thought that the above poem was written by Thomas Wyatt when he left the court of King Henry VIII after thinking he had got too close to Ann Boleyn.

But as for me, hélas, I may no more.

The vain travail hath wearied me so sore,

I am of them that farthest cometh behind.

Yet may I by no means my wearied mind

Draw from the deer, but as she fleeth afore

Fainting I follow. I leave off therefore,

Sithens in a net I seek to hold the wind.

Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt,

As well as I may spend his time in vain.

And graven with diamonds in letters plain

There is written, her fair neck round about:

Noli me tangere, for Caesar's I am,

And wild for to hold, though I seem tame.

Thomas Wyatt

It is thought that the above poem was written by Thomas Wyatt when he left the court of King Henry VIII after thinking he had got too close to Ann Boleyn.

36baswood

Graven with Diamonds: The many lives of Thomas Wyatt Courtier, Poet, Assassin, Spy By Nicola Shulman

Sir Thomas Wyatt known today as one of the leading poets from the early Tudor period led a colourful life as can be seen from the eye grabbing title of Nicola Shulman’s biography. I was tempted to say that the tile was the best thing about the book, but that would be unfair on Shulman whose vivid account of the goings on at King Henry VIII’s court finally won me over. From the fall of Anne Boleyn until Henry VIII’s demise to survive as a courtier then; being an assassin and a spy would have stood you in good stead, but Shulman argues that Wyatts poetic skills were equally important. Shulman’s biography: if not a panegyric is certainly a very flattering portrait of a man who did what was necessary to survive. Shulman claims his poetry in some respects is the work of a genius and his poems are perhaps some of the greatest works of art ever made, this is in contrast to many literary critics who see Wyatt as a conventional poet who rarely if ever reached the heights that Shulman claims for him.

Thomas Wyatt never reached the inner circle of Henry VIII’s courtiers but he was liked and respected. He was the son of one of the leading families of the time and his father was a courtier. He was a skilled poet and songsmith and many of his early love poems he would have sung accompanying himself on the lute for the pleasure of his fellows. He was quick witted and amusing company as well as having all the social skills necessary to maintain his position, but this did not stop him getting into trouble as it was a case of which faction within the court that got the ear of the king. Wyatt as a man holding reformist views was associated with the Boleyn family and when Anne was arrested along with four men accused of being her lovers, he found himself in the Tower of London as well. He was fortunate no charges were brought against him and he was eventually released. (the others were all executed). He probably owed his good fortune to Thomas Cromwell who was quick to make use of him on his release. He became a diplomat or one of Cromwell’s agents sent first to Spain and then to France. He was eventually relieved of his duties but then found himself in more serious trouble as the catholic Howard family gained the upper hand at court and he was accused of consorting with traitors abroad. Once again in the Tower but now indicted under an act of attainder, his goods and property were all under forfeit and his family and his servants were all at the king’s mercy. Execution was the usual outcome but Wyatt once again got lucky because the young queen Catherine Howard asking for clemency. Wyatt once again found his diplomatic skills in demand and he died in service.

Nicola Shulman’s modus operandi is to tell the story with insight gained from Wyatt’s poetry. She claims that Wyatt’s poetry has translucent properties that reveal far more than many critics have recognised. She uses examples that she claims shed new light, or perhaps contain secret messages to participants in the story and while poems, (but more usually extracts from poems) can be read in this way, for me they provide some food for thought, but little more. I suppose that if you are going to write a biography about a man who is remembered for his poetry then using that poetry where you can, to enhance the story is an interesting idea, especially on events that have been told so often and for which there is limited documentation (I am thinking here of the fall and execution of Ann Boleyn.). If it serves the purpose of reading those poems in a new light then the book has been useful.

Nicola Shulman does have her heroes, but that sometimes happens when writing a biography and she can get a little sidetracked; as at one point I wondered if I was reading a biography of Ann Boleyn, but this is an excellent waltz through a fascinating period of history. I don’t think it offers much in the way of new incites to the events themselves, but it does raise some interesting points about the use and value of the poems. Wyatt’s poems would not have been printed during his lifetime, but would have existed in manuscript form, they would have been recited and sung to people at Henry’s court (people in positions of power) and to think of them as containing coded messages is an interesting concept. Shulman lists her primary and secondary sources and provides an index. She does not take any liberties with the historical facts as far as I can see and I enjoyed the read and so 3.5 stars.

Sir Thomas Wyatt known today as one of the leading poets from the early Tudor period led a colourful life as can be seen from the eye grabbing title of Nicola Shulman’s biography. I was tempted to say that the tile was the best thing about the book, but that would be unfair on Shulman whose vivid account of the goings on at King Henry VIII’s court finally won me over. From the fall of Anne Boleyn until Henry VIII’s demise to survive as a courtier then; being an assassin and a spy would have stood you in good stead, but Shulman argues that Wyatts poetic skills were equally important. Shulman’s biography: if not a panegyric is certainly a very flattering portrait of a man who did what was necessary to survive. Shulman claims his poetry in some respects is the work of a genius and his poems are perhaps some of the greatest works of art ever made, this is in contrast to many literary critics who see Wyatt as a conventional poet who rarely if ever reached the heights that Shulman claims for him.

Thomas Wyatt never reached the inner circle of Henry VIII’s courtiers but he was liked and respected. He was the son of one of the leading families of the time and his father was a courtier. He was a skilled poet and songsmith and many of his early love poems he would have sung accompanying himself on the lute for the pleasure of his fellows. He was quick witted and amusing company as well as having all the social skills necessary to maintain his position, but this did not stop him getting into trouble as it was a case of which faction within the court that got the ear of the king. Wyatt as a man holding reformist views was associated with the Boleyn family and when Anne was arrested along with four men accused of being her lovers, he found himself in the Tower of London as well. He was fortunate no charges were brought against him and he was eventually released. (the others were all executed). He probably owed his good fortune to Thomas Cromwell who was quick to make use of him on his release. He became a diplomat or one of Cromwell’s agents sent first to Spain and then to France. He was eventually relieved of his duties but then found himself in more serious trouble as the catholic Howard family gained the upper hand at court and he was accused of consorting with traitors abroad. Once again in the Tower but now indicted under an act of attainder, his goods and property were all under forfeit and his family and his servants were all at the king’s mercy. Execution was the usual outcome but Wyatt once again got lucky because the young queen Catherine Howard asking for clemency. Wyatt once again found his diplomatic skills in demand and he died in service.

Nicola Shulman’s modus operandi is to tell the story with insight gained from Wyatt’s poetry. She claims that Wyatt’s poetry has translucent properties that reveal far more than many critics have recognised. She uses examples that she claims shed new light, or perhaps contain secret messages to participants in the story and while poems, (but more usually extracts from poems) can be read in this way, for me they provide some food for thought, but little more. I suppose that if you are going to write a biography about a man who is remembered for his poetry then using that poetry where you can, to enhance the story is an interesting idea, especially on events that have been told so often and for which there is limited documentation (I am thinking here of the fall and execution of Ann Boleyn.). If it serves the purpose of reading those poems in a new light then the book has been useful.

Nicola Shulman does have her heroes, but that sometimes happens when writing a biography and she can get a little sidetracked; as at one point I wondered if I was reading a biography of Ann Boleyn, but this is an excellent waltz through a fascinating period of history. I don’t think it offers much in the way of new incites to the events themselves, but it does raise some interesting points about the use and value of the poems. Wyatt’s poems would not have been printed during his lifetime, but would have existed in manuscript form, they would have been recited and sung to people at Henry’s court (people in positions of power) and to think of them as containing coded messages is an interesting concept. Shulman lists her primary and secondary sources and provides an index. She does not take any liberties with the historical facts as far as I can see and I enjoyed the read and so 3.5 stars.

37thorold

>36 baswood: With all those revealing translucent poems, I can't help visualising Wyatt forgetting to close the blind in the bathroom (where he moisteth and washeth), with the court looking on horrified as the water pours off his hipster beard... I trust it was Schulman's image and not yours!

(Sorry, after visiting Hever Castle, world headquarters of the Anne Boleyn tat industry, last week, it's a bit difficult to take anything Tudor seriously any more...)

(Sorry, after visiting Hever Castle, world headquarters of the Anne Boleyn tat industry, last week, it's a bit difficult to take anything Tudor seriously any more...)

38Nickelini

>36 baswood:. Interesting!

"They Flee From Me" is one of my favourite poems. Don't really know why.

>37 thorold: So Hever Castle isn't worth the visit? We almost went there, but went to Knole House instead. I've often wondered what I missed.

"They Flee From Me" is one of my favourite poems. Don't really know why.

>37 thorold: So Hever Castle isn't worth the visit? We almost went there, but went to Knole House instead. I've often wondered what I missed.

39sibylline

Very much enjoying the reviews of the Howard and Wyatt bios -- and a taste of their poetry.

40thorold

>38 Nickelini: We went to Hever instead of Knole, so hard to say! The gardens and the outside of the castle are worth seeing, but the interior is all set up as a kind of bad taste Anne Boleyn theme park (waxworks, background music playing Greensleeves...), apart from a few rooms done up in country hotel style by the Astors.

41dchaikin

>36 baswood: another excellent, enlightening review.

42rebeccanyc

>36 baswood: >41 dchaikin: Ditto what Dan said.

43kidzdoc

Great side by side reviews of The Meursault Investigation and Children of the New World, Barry. I was one of those who had a positive opinion of Daoud's novel, but your comments are making me reconsider my thoughts about it. I've owned Djebar's novel for several years, but I still haven't gotten to it. Hopefully I can do so later this year.

44NanaCC

Barry, I'm just catching up after vacation, and as always love your reviews. I thought the Shardlake series was really quite good, and the historical elements seem very accurate. For those who don't think a mystery about this time period can work, you will just have to try one to see how good they really are.

45baswood

They Flee From Me

BY SIR THOMAS WYATT

They flee from me that sometime did me seek

With naked foot, stalking in my chamber.

I have seen them gentle, tame, and meek,

That now are wild and do not remember

That sometime they put themself in danger

To take bread at my hand; and now they range,

Busily seeking with a continual change.

Thanked be fortune it hath been otherwise

Twenty times better; but once in special,

In thin array after a pleasant guise,

When her loose gown from her shoulders did fall,

And she me caught in her arms long and small;

Therewithall sweetly did me kiss

And softly said, “Dear heart, how like you this?”

It was no dream: I lay broad waking.

But all is turned thorough my gentleness

Into a strange fashion of forsaking;

And I have leave to go of her goodness,

And she also, to use newfangleness.

But since that I so kindly am served

I would fain know what she hath deserved.

BY SIR THOMAS WYATT

They flee from me that sometime did me seek

With naked foot, stalking in my chamber.

I have seen them gentle, tame, and meek,

That now are wild and do not remember

That sometime they put themself in danger

To take bread at my hand; and now they range,

Busily seeking with a continual change.

Thanked be fortune it hath been otherwise

Twenty times better; but once in special,

In thin array after a pleasant guise,

When her loose gown from her shoulders did fall,

And she me caught in her arms long and small;

Therewithall sweetly did me kiss

And softly said, “Dear heart, how like you this?”

It was no dream: I lay broad waking.

But all is turned thorough my gentleness

Into a strange fashion of forsaking;

And I have leave to go of her goodness,

And she also, to use newfangleness.

But since that I so kindly am served

I would fain know what she hath deserved.

46Caroline_McElwee

>36 baswood: I do have that volume, time to set the dogs loose for to hunt!

47thorold

>45 baswood: Thanks! - I haven't read that poem for ages, and didn't remember anything except the marvellous opening line.

Looking at it now, it strikes me (i) how difficult it is to make it read into modern English - you keep hitting constructions that don't go the way you want to and sounds (both rhymes and stresses) that have obviously changed (we need a good actor to read it for us, really) and (ii) how I obviously never bothered to work out what he means by "newfangleness". That set me off on a trawl through the OED, and I realised that the "fang" bit is from the English verb cognate with modern German "fangen" (to catch), so newfangleness is inconstancy in the sense of a tendency to catch at new things. I'm sure everyone else knew this already, but at least I've learnt something new(fangled?).

Looking at it now, it strikes me (i) how difficult it is to make it read into modern English - you keep hitting constructions that don't go the way you want to and sounds (both rhymes and stresses) that have obviously changed (we need a good actor to read it for us, really) and (ii) how I obviously never bothered to work out what he means by "newfangleness". That set me off on a trawl through the OED, and I realised that the "fang" bit is from the English verb cognate with modern German "fangen" (to catch), so newfangleness is inconstancy in the sense of a tendency to catch at new things. I'm sure everyone else knew this already, but at least I've learnt something new(fangled?).

48baswood

>47 thorold: I believe that newfangleness also had a slightly different meaning in the 16th century. It more than hinted that the catcher of new things was indeed a promiscuous person, moving from one lover to the next.

One of the pleasures I find in reading poetry from this period is the change of meaning of some of the words. Reading it with a 21st century vocabulary can give the poem a dimension that would have been foreign to the 16th century writer. Sometimes this makes nonsense of the poem, but at other times it gives it almost another life.

Two examples "And she caught me in her arms long and small" makes no sense until you realise that small means slender.

"But since that I am so kindly served" has many inflections. Service in courtly love terms meant to be of service to someone in the sense of looking out for them or helping them in someway, but service could also mean to provide sexual satisfaction. You can read this line with the idea that Wyatt is being ironic with the word kindly.

Reading the poem with its modern spelling, but still maintaining its 16th century construction or word order does not always work and I find reading some of them with the original spelling makes it flow better. But you are right in pointing out that Wyatt did not always get his stresses or word order to flow well, and he has garnered a fair amount of criticism for this over the years.

One of the pleasures I find in reading poetry from this period is the change of meaning of some of the words. Reading it with a 21st century vocabulary can give the poem a dimension that would have been foreign to the 16th century writer. Sometimes this makes nonsense of the poem, but at other times it gives it almost another life.

Two examples "And she caught me in her arms long and small" makes no sense until you realise that small means slender.

"But since that I am so kindly served" has many inflections. Service in courtly love terms meant to be of service to someone in the sense of looking out for them or helping them in someway, but service could also mean to provide sexual satisfaction. You can read this line with the idea that Wyatt is being ironic with the word kindly.

Reading the poem with its modern spelling, but still maintaining its 16th century construction or word order does not always work and I find reading some of them with the original spelling makes it flow better. But you are right in pointing out that Wyatt did not always get his stresses or word order to flow well, and he has garnered a fair amount of criticism for this over the years.

50baswood

The Poetry of Sir Thomas Wyatt: A Selection and Study by E. M. W. Tillyard

Silver Poets of the Sixteenth Century

Sir Thomas Wyatt and his poems by William Edward Simonds

Sir Thomas Wyatt along with Henry Howard Earl of Surrey are the only two poets given their full name in Tottel’s Miscellany (The first anthology of printed poems to be published; 1557). The Miscellany was enormously popular running to a second print just six weeks after the first and so it probably went a long way to establishing Wyatt’s place in the canon of English poetry. His poems were not published during his lifetime, but would have been circulated in manuscript form among a select group of people who were courtiers to Henry VIII. Many of his pieces would not have been recognised as poems, but rather as songs and because he was by all accounts an accomplished lute player and songwriter he would have been a popular figure at court well able to entertain his friends. Tottel by printing the pieces as poems took them out of the hot house of the courtiers world and made them available to the general public (those that could read and who could buy books).

There are 95 poems by Wyatt in the Miscellany and another 100 or more have been found in private collections and so there is a large body of his work that is available and there are at least two fairly modern collections. The majority of the pieces could be described as lyrics or songs and many of these were based around the idea of courtly love, which can be defined as:

a highly conventionalized medieval tradition of love between a knight and a married noblewoman, first developed by the troubadours of southern France and extensively employed in European literature of the time. The love of the knight for his lady was regarded as an ennobling passion and the relationship was typically unconsummated.

This is a typical example by Wyatt:

To wish and want and not obtain,

To seek and sue ease of my pain,

Since all that ever I do is vain

What may it avail me?

Although I strive both day and hour

Against the stream with all my power,

If fortune list yet for to lour

What may it avail me?

If willingly I suffer woe,

If from the fire me list not go,

If then I burn to plain me so,

What may it avail me?

And if the harm that I suffer

Be run too far out of measure,

To seek for help any further

What may it avail me?

What though each heart that heareth me plain

Pityeth and plaineth for my pain,

If I no less in grief remain

What may it avail me?

Yea, though the want of my relief

Displease the causer of my grief,

Since I remain still in mischief

What may it avail me?

Such cruel chance doth so me threat

Continually inward to fret.

Then of release for to treat

What may it avail me?

Fortune is deaf unto my call.

My torment moveth her not at all.

And though she turn as doth a ball

What may it avail me?

For in despair there is no rede.

To want of ear speech is no speed.

To linger still alive as dead

What may it avail me?

I can imagine this being put to music and being enjoyed by friends that would have been steeped in the traditions of courtly love.

However when looking back on songs and lyrics from the 16th century it is the poets who break with tradition and point the way to something new that grabs our attention and Wyatt certainly did this.

He introduced a number of poems in sonnet form based on his free translations of the Italian Renaissance poet Petrarch. He had to adapt the Italian language to 16th century English and also reinvent a rhyming scheme that would fit. His attempts were not always successful; (of the 20 or so sonnets that I have read about a half of these sound clunky and are difficult to read aloud) but he laid a template for others to follow. He also experimented with other forms and rhyming schemes, again with varying degrees of success. He wrote epigrams which might have sounded witty and entertaining in the 16th century, but sound laboured to my ears. He made translations of the penitential psalms and he also left us three satires based on his experiences as a courtier to Henry VIII.

E M W Tillyard in his selection and study of Wyatts poems says that there is little evidence of a break with medieval tradition. Although he chooses Italian themes he is bound by the English tradition of song making. I can see his point but I think in many of the lyrics Wyatt’s individual voice can be detected and this makes him readable for 21st century readers. William Edward Symonds in his study of the poems attempts to place the courtly love poems in some sort of order, so as to make of them a collection that depicts a courtly love affair. It can be done because the poems go through the whole gamut of such an affair; the moment when love hits, the eager anticipation, the offer to to the lady of faithful service, the pain of rejection and the the ruminations on a life wasted. However this was not the intention of Wyatt and although it sort of works it sounds artificial.