lyzard's list: letting the numbers take care of themselves - Part 3

This is a continuation of the topic lyzard's list: letting the numbers take care of themselves - Part 2.

This topic was continued by lyzard's list: letting the numbers take care of themselves - Part 4.

Talk75 Books Challenge for 2014

Join LibraryThing to post.

This topic is currently marked as "dormant"—the last message is more than 90 days old. You can revive it by posting a reply.

1lyzard

My new thread-topper is the Cooktown orchid, which was adopted as the floral emblem of Queensland in 1959. The orchid is native to northern Queensland, although it is not a rainforest species, and in the wild flowers during the dry season. The flowers range from mauve through shades of pink and occasionally white, with variants that have pale petals but a darker heart. The individual flowers are about 5 cm in diameter, and appear on spikes in bunches of up to twenty. It is a popular garden and house plant as it is hardy for an orchid and can be induced to flower throughout the year.

2lyzard

WELCOME TO 2014!

Hello, all, and welcome to my 2014 thread. I'm Liz, and this will be my fourth full year in the 75-ers group, after joining towards the end of 2010.

Because of the relative obscurity of many of the books I read, I tend to get less visitors / conversation than many of the 75-ers, so anyone who drops by this thread can be certain of a welcome bordering on the hysterical.

In 2013 I set myself a target of 150 books for the year, and while I reached it (yay!), I was feeling constrained with my reading towards the end; avoiding chunksters and so on, out of consciousness of time and numbers. So this year I've decided to take a more relaxed approached to things, and let the numbers take care of themselves.

Usually, I have several main reading "themes". I read for a blog project; I have more ongoing series than I can count; I am reading early detective fiction to examine the evolution of the genre; and I am fortunate enough to be involved in various group and tutored reads, chiefly of 19th century literature. My tastes run to the old, obscure and forgotten - which is fun for me, but tends to restrict conversation!

This year, however, I want to shake things up a bit by reading through some of my long untouched books, with a view to pruning my collection. This will be predominantly horror, fantasy and crime fiction from the mid-1990s (I was going through "a phase").

Similarly, I may finally tackle some of the many classics I have accumulated over the years but never actually gotten around to reading.

I have a blog, A Course Of Steady Reading, where the main thrust is the examination of the development of the English novel, from 1660 onwards. In addition, I am looking at the roots of the Gothic novel, reading certain 18th and 19th century authors in depth, and reviewing novels published between 1751 - 1930 selected randomly from my wishlist.

This year I will be undertaking a new project which will involve working through as-yet unread Virago Press releases in chronological order by original publication date. I am delighted to say that Heather (souloftherose) will be joining me for at least some of this project, and anyone else who cares to join in would be most welcome!

Another of my obsessions is "books from a particular year". Towards the end of last year I more or less wrapped up 1931, and will soon be launching into - yes, you guessed it! - 1932.

I am also one of several people working through the detective fiction of Agatha Christie, and the historical romances of Georgette Heyer - another project where anyone is welcome. This is a leisurely pursuit involving one of each per month, on average. These are re-reads for me, while others are just discovering these two authors.

This may also be the year I finally get around to reading the Harry Potter books...

So to summarise:

Main reading themes for 2014:

* Blog reading

* Series and sequels

* Early detective fiction

* Chronological Virago

* Books off the shelves

* 1932

* Agatha Christie / Georgette Heyer re-reads

* Group / tutored reads

Hello, all, and welcome to my 2014 thread. I'm Liz, and this will be my fourth full year in the 75-ers group, after joining towards the end of 2010.

Because of the relative obscurity of many of the books I read, I tend to get less visitors / conversation than many of the 75-ers, so anyone who drops by this thread can be certain of a welcome bordering on the hysterical.

In 2013 I set myself a target of 150 books for the year, and while I reached it (yay!), I was feeling constrained with my reading towards the end; avoiding chunksters and so on, out of consciousness of time and numbers. So this year I've decided to take a more relaxed approached to things, and let the numbers take care of themselves.

Usually, I have several main reading "themes". I read for a blog project; I have more ongoing series than I can count; I am reading early detective fiction to examine the evolution of the genre; and I am fortunate enough to be involved in various group and tutored reads, chiefly of 19th century literature. My tastes run to the old, obscure and forgotten - which is fun for me, but tends to restrict conversation!

This year, however, I want to shake things up a bit by reading through some of my long untouched books, with a view to pruning my collection. This will be predominantly horror, fantasy and crime fiction from the mid-1990s (I was going through "a phase").

Similarly, I may finally tackle some of the many classics I have accumulated over the years but never actually gotten around to reading.

I have a blog, A Course Of Steady Reading, where the main thrust is the examination of the development of the English novel, from 1660 onwards. In addition, I am looking at the roots of the Gothic novel, reading certain 18th and 19th century authors in depth, and reviewing novels published between 1751 - 1930 selected randomly from my wishlist.

This year I will be undertaking a new project which will involve working through as-yet unread Virago Press releases in chronological order by original publication date. I am delighted to say that Heather (souloftherose) will be joining me for at least some of this project, and anyone else who cares to join in would be most welcome!

Another of my obsessions is "books from a particular year". Towards the end of last year I more or less wrapped up 1931, and will soon be launching into - yes, you guessed it! - 1932.

I am also one of several people working through the detective fiction of Agatha Christie, and the historical romances of Georgette Heyer - another project where anyone is welcome. This is a leisurely pursuit involving one of each per month, on average. These are re-reads for me, while others are just discovering these two authors.

This may also be the year I finally get around to reading the Harry Potter books...

So to summarise:

Main reading themes for 2014:

* Blog reading

* Series and sequels

* Early detective fiction

* Chronological Virago

* Books off the shelves

* 1932

* Agatha Christie / Georgette Heyer re-reads

* Group / tutored reads

3lyzard

********************************************************

Currently reading:

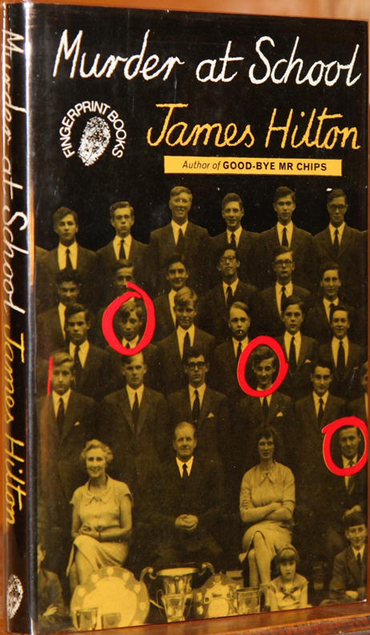

Murder At School by James Hilton (1931)

4lyzard

January:

1. Munster Abbey, A Romance: Interspersed With Reflections On Virtue And Morality by Sir Samuel Egerton Leigh (1797)

2. The Senator's Lady by Mathilde Eiker (1932)

3. The Girl, The Gold Watch & Everything by John D. MacDonald (1962)

4. The Admirable Carfew by Edgar Wallace (1914)

5. The Talisman Ring by Georgette Heyer (1936)

6. The House By The Road by Charles J. Dutton (1924)

7. The Gray Phantom by Herman Landon (1921)

8. The Million-Dollar Suitcase by Alice MacGowan and Perry Newberry (1922)

9. The Prisoner Of Zenda by Anthony Hope (1894)

10. Trilby by George Du Maurier (1894)

11. Partners In Crime by Agatha Christie (1929)

February:

12. May It Please Your Lordship by E. S. Turner (1971)

13. Bernard Leslie; or, A Tale Of The Last Ten Years by William Gresley (1942)

14. Japanese Tales Of Mystery And Imagination by Egogawa Rampo (1956)

15. Inspector French's Greatest Case by Freeman Wills Crofts (1924)

16. Suffer And Be Still: Women In The Victorian Age by Martha Vicinus (ed.) (1972)

17. Thank Heaven Fasting by E. M. Delafield (1932)

18. The Man In The Dark by John Alexander Ferguson (1928)

19. An Infamous Army by Georgette Heyer (1937)

20. The Secret Of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton (1927)

21. The History Of The Nun; or, The Fair Vow-Breaker by Aphra Behn (1689)

22. The Mysterious Mr Quin by Agatha Christie (1930)

March:

23. The Last Chronicle Of Barset by Anthony Trollope (1867)

24. The Noose by Philip MacDonald (1930)

25. Yesterday's Woman: Domestic Realism In The English Novel by Vineta Colby (1974)

26. As We Are: A Modern Revue by E. F. Benson (1932)

27. The Princess Of All Lands by Russell Kirk (1979)

28. The Claverton Mystery by John Rhode (1933)

29. The Death Of A Millionaire by G. D. H. and Margaret Cole (1925)

30. The Murder At The Vicarage by Agatha Christie (1930)

31. A Modern Hero by Louis Bromfield (1932)

April:

32. The Corinthian by Georgette Heyer (1940)

33. The Scandal Of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton (1935)

34. Venusberg by Anthony Powell (1932)

35. The Adventures Of Miss Sophia Berkley by Anonymous (1760)

36. The Silver-Fork School: Novels Of Fashion Preceding Vanity Fair by Matthew Whiting Rosa (1936)

37. The Ultimate Werewolf by Byron Preiss (ed.) (1992)

38. Victorian People And Ideas: A Companion For The Modern Reader Of Victorian Literature by Richard D. Altick (1973)

39. Miss Pinkerton by Mary Roberts Rinehart (1932)

40. Mr Fortune's Trials by H. C. Bailey (1925)

41. The Sittaford Mystery by Agatha Christie (1931)

42. Contango by James Hilton (1932)

1. Munster Abbey, A Romance: Interspersed With Reflections On Virtue And Morality by Sir Samuel Egerton Leigh (1797)

2. The Senator's Lady by Mathilde Eiker (1932)

3. The Girl, The Gold Watch & Everything by John D. MacDonald (1962)

4. The Admirable Carfew by Edgar Wallace (1914)

5. The Talisman Ring by Georgette Heyer (1936)

6. The House By The Road by Charles J. Dutton (1924)

7. The Gray Phantom by Herman Landon (1921)

8. The Million-Dollar Suitcase by Alice MacGowan and Perry Newberry (1922)

9. The Prisoner Of Zenda by Anthony Hope (1894)

10. Trilby by George Du Maurier (1894)

11. Partners In Crime by Agatha Christie (1929)

February:

12. May It Please Your Lordship by E. S. Turner (1971)

13. Bernard Leslie; or, A Tale Of The Last Ten Years by William Gresley (1942)

14. Japanese Tales Of Mystery And Imagination by Egogawa Rampo (1956)

15. Inspector French's Greatest Case by Freeman Wills Crofts (1924)

16. Suffer And Be Still: Women In The Victorian Age by Martha Vicinus (ed.) (1972)

17. Thank Heaven Fasting by E. M. Delafield (1932)

18. The Man In The Dark by John Alexander Ferguson (1928)

19. An Infamous Army by Georgette Heyer (1937)

20. The Secret Of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton (1927)

21. The History Of The Nun; or, The Fair Vow-Breaker by Aphra Behn (1689)

22. The Mysterious Mr Quin by Agatha Christie (1930)

March:

23. The Last Chronicle Of Barset by Anthony Trollope (1867)

24. The Noose by Philip MacDonald (1930)

25. Yesterday's Woman: Domestic Realism In The English Novel by Vineta Colby (1974)

26. As We Are: A Modern Revue by E. F. Benson (1932)

27. The Princess Of All Lands by Russell Kirk (1979)

28. The Claverton Mystery by John Rhode (1933)

29. The Death Of A Millionaire by G. D. H. and Margaret Cole (1925)

30. The Murder At The Vicarage by Agatha Christie (1930)

31. A Modern Hero by Louis Bromfield (1932)

April:

32. The Corinthian by Georgette Heyer (1940)

33. The Scandal Of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton (1935)

34. Venusberg by Anthony Powell (1932)

35. The Adventures Of Miss Sophia Berkley by Anonymous (1760)

36. The Silver-Fork School: Novels Of Fashion Preceding Vanity Fair by Matthew Whiting Rosa (1936)

37. The Ultimate Werewolf by Byron Preiss (ed.) (1992)

38. Victorian People And Ideas: A Companion For The Modern Reader Of Victorian Literature by Richard D. Altick (1973)

39. Miss Pinkerton by Mary Roberts Rinehart (1932)

40. Mr Fortune's Trials by H. C. Bailey (1925)

41. The Sittaford Mystery by Agatha Christie (1931)

42. Contango by James Hilton (1932)

5lyzard

Books in transit:

On interlibrary loan / storage request:

Purchased and shipped:

The Mystery Of The Evil Eye by Anthony Wynne

On loan:

**The Scandal Of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton (22/04/2014)

**The Silver-Fork School: Novels Of Fashion Preceding Vanity Fair by Matthew Whiting Rosa (28/04/2014)

The Best Circles: Society, Etiquette And The Season by Leonore Davidoff (04/07/2014)

Love-Letters Between A Nobleman And His Sister by Aphra Behn (04/07/2014)

Pamela's Daughters by Robert Palfrey Utter and Gwendolyn Bridges Needham (04/07/2014)

The Early Victorians At Home by Elizabeth Burton (04/07/2014)

The Social Novel In England, 1830-1850 by Louis François Cazamian, translated by Martin Fido (04/07/2014)

*Victorian People And Ideas by Richard Altick (04/07/2014)

Three Houses by Angela Thirkell (17/07/2014)

Was It Murder? by James Hilton (17/07/2014)

The Man Of Property by John Galsworthy (17/07/2014)

The Gods Arrive by Edith Wharton (17/07/2014)

Track down:

Handfasted by Catherine Helen Spence {interlibrary loan}

Quintus Servinton by Henry Savery (aka The Bitter Bread Of Banishment) {Fisher Library / storage & new edition}

The Final War by Louis Tracy {Internet Archive}

Guilty Bonds by William Le Queux {Project Gutenberg}

An Australian Heroine by Rosa Praed {Internet Archive}

The Last Lemurian by G. Firth Scott {Project Gutenberg Australia}

An Australian Girl by Catherine Martin {interlibrary loan}

On interlibrary loan / storage request:

Purchased and shipped:

The Mystery Of The Evil Eye by Anthony Wynne

On loan:

**The Scandal Of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton (22/04/2014)

**The Silver-Fork School: Novels Of Fashion Preceding Vanity Fair by Matthew Whiting Rosa (28/04/2014)

The Best Circles: Society, Etiquette And The Season by Leonore Davidoff (04/07/2014)

Love-Letters Between A Nobleman And His Sister by Aphra Behn (04/07/2014)

Pamela's Daughters by Robert Palfrey Utter and Gwendolyn Bridges Needham (04/07/2014)

The Early Victorians At Home by Elizabeth Burton (04/07/2014)

The Social Novel In England, 1830-1850 by Louis François Cazamian, translated by Martin Fido (04/07/2014)

*Victorian People And Ideas by Richard Altick (04/07/2014)

Three Houses by Angela Thirkell (17/07/2014)

Was It Murder? by James Hilton (17/07/2014)

The Man Of Property by John Galsworthy (17/07/2014)

The Gods Arrive by Edith Wharton (17/07/2014)

Track down:

Handfasted by Catherine Helen Spence {interlibrary loan}

Quintus Servinton by Henry Savery (aka The Bitter Bread Of Banishment) {Fisher Library / storage & new edition}

The Final War by Louis Tracy {Internet Archive}

Guilty Bonds by William Le Queux {Project Gutenberg}

An Australian Heroine by Rosa Praed {Internet Archive}

The Last Lemurian by G. Firth Scott {Project Gutenberg Australia}

An Australian Girl by Catherine Martin {interlibrary loan}

6lyzard

Ongoing series and sequels:

(1866 - 1876) **Emile Gaboriau - Monsieur Lecoq - The Widow Lerouge (1/6) {ManyBooks}

(1867 - 1905) **Martha Finley - Elsie Dinsmore - Holidays At Roselands (2/28) {ManyBooks}

(1878 - 1917) **Anna Katharine Green - Ebenezer Gryce - Behind Closed Doors (5/12) {Book Depository}

(1896 - 1909) **Melville Davisson Post - Randolph Mason - The Corrector Of Destinies (3/3) {Internet Archive}

(1894 - 1898) **Anthony Hope - Ruritania - The Heart Of Princess Osra (2/3) {Project Gutenberg}

(1895 - 1901) **Guy Newell Boothby - Dr Nikola - A Bid For Fortune (1/5) {Project Gutenberg}

(1897 - 1900) **Anna Katharine Green - Amelia Butterworth - That Affair Next Door (1/3) {Fisher Library}

(1900 - 1974) *Ernest Bramah - Kai Lung - The Wallet Of Kai Lung (1/6) {ManyBooks}

(1901 - 1919) **Carolyn Wells - Patty Fairfield - Patty's Summer Days (4/17) {ManyBooks}

(1903 - 1904) **Louis Tracy - Reginald Brett - A Fatal Legacy (aka The Stowmarket Mystery) (1/2) {ManyBooks}

(1904 - ????) *Louis Tracy - Winter and Furneaux - The Albert Gate Mystery (1/?) {ManyBooks}

(1905 - 1925) **Baroness Orczy - The Old Man In The Corner - Unravelled Knots (3/3) {Project Gutenberg Australia}}

(1905 - 1928) **Edgar Wallace - The Just Men - The Just Men Of Cordova (3/6) {ManyBooks}

(1906 - 1930) **John Galsworthy - The Forsyte Saga - The Man Of Property (1/11) {Fisher Library}

(1907 - 1912) **Carolyn Wells - Marjorie - Marjorie's Vacation (1/6) {ManyBooks}

(1907 - 1942) *R. Austin Freeman - Dr John Thorndyke - The D'Arblay Mystery (13/26) {Feedbooks}

(1907 - 1941) *Maurice Leblanc - Arsene Lupin - Arsene Lupin, Gentleman Burglar (1/21) {ManyBooks}

(1908 - 1924) **Margaret Penrose - Dorothy Dale - Dorothy Dale: A Girl Of Today (1/13) {ManyBooks}

(1909 - 1942) *Carolyn Wells - Fleming Stone - Raspberry Jam (11/49) {ManyBooks}

(1910 - 1936) *Arthur B. Reeve - Craig Kennedy - The Social Gangster (5/11) {ManyBooks}

(1910 - 1946) A. E. W. Mason - Inspector Hanaud - They Wouldn't Be Chessmen (4/5) {AbeBooks}

(1910 - ????) *Edgar Wallace - Inspector Smith - Kate Plus Ten (3/?) {Project Gutenberg Australia}

(1910 - 1930) **Edgar Wallace - Inspector Elk - The Fellowship Of The Frog (2/6?) {ebook}

(1910 - ????) *Thomas Hanshew - Cleek - Cleek's Government Cases (3/?) {Internet Archive / Mobilereads}

(1910 - 1918) *John McIntyre - Ashton-Kirk - Ashton-Kirk: Investigator (1/4) {ManyBooks / Project Gutenberg}

(1910 - 1931) *Grace S. Richmond - Red Pepper Burns - Red Pepper Burns (1/6) {ManyBooks}

(1911 - 1935) *G. K. Chesterton - Father Brown - The Scandal Of Father Brown (5/5) {branch transfer}

(1911 - 1937) *Mary Roberts Rinehart - Letitia Carberry - Tish Plays The Game (4/5) {GooglePlay}

(1913 - 1934) *Alice B. Emerson - Ruth Fielding - Ruth Fielding At Sunrise Farm (7/30) {Project Gutenberg}

(1913 - 1973) Sax Rohmer - Fu-Manchu - The Mask Of Fu-Manchu (5/14) {interlibrary loan}

(1914 - 1950) Mary Roberts Rinehart - Hilda Adams - Haunted Lady (4/5) {Owned}

(1914 - 1934) *Ernest Bramah - Max Carrados - The Eyes Of Max Carrados (2/4) {interlibrary loan}

(1916 - 1941) John Buchan - Edward Leithen - Sick Heart River (5/5) {Fisher Library}

(1916 - 1917) **Carolyn Wells - Alan Ford - Faulkner's Folly (2/2) {Book Depository}

(1918 - 1923) **Carolyn Wells - Pennington Wise - The Room With The Tassels (1/8) {Internet Archive / Book Depository}

(1919 - 1966) *Lee Thayer - Peter Clancy - The Sinister Mark (5/60) {owned}

(1920 - 1939) E. F. Benson - Mapp And Lucia - Lucia's Progress (5/6) {Fisher Library}

(1920 - 1948) *H. C. Bailey - Reggie Fortune - Mr Fortune, Please (4/23) {academic loan}

(1920 - 1949) William McFee - Spenlove - The Beachcomber - (3/6) {AbeBooks}

(1920 - 1932) *Alice B. Emerson - Betty Gordon - Betty Gordon At Bramble Farm (1/15) {ManyBooks}

(1920 - 1975) *Agatha Christie - Hercule Poirot - Peril At End House (7/39) {owned}

(1921 - 1929) **Charles J. Dutton - John Bartley - The Second Bullet (5/9) {expensive}

(1921 - 1925) **Herman Landon - The Gray Phantom - The Gray Phantom's Return (2/5) {Project Gutenberg}

(1922 - 1973) *Agatha Christie - Tommy and Tuppence - N. Or M.? (3/5) {owned}

(1922 - 1927) *Alice MacGowan and Perry Newberry - Jerry Boyne - The Mystery Woman (2/5) {Amazon, eBay?}

(1923 - 1937) Dorothy L. Sayers - Lord Peter Wimsey - Have His Carcase (8/15) {Fisher Library}

(1923 - 1924) **Carolyn Wells - Lorimer Lane - The Fourteenth Key (2/2) {Amazon domestic}

(1924 - 1959) * / ***Philip MacDonald - Colonel Anthony Gethryn - Persons Unknown (aka "The Maze") (5/24) {academic loan}

(1924 - 1957) *Freeman Wills Crofts - Inspector French - The Cheyne Mystery (2/30) {Fisher Library}

(1924 - 1935) *Francis D. Grierson - Inspector Sims and Professor Wells - The Limping Man (1/13) {owned}

(1924 - 1940) *Lynn Brock - Colonel Gore - The Deductions Of Colonel Gore (1/12) {owned}

(1924 - 1933) *Herbert Adams - Jimmie Haswell - The Secret Of Bogey House (1/9) {owned}

(1924 - 1944) *A. Fielding - Inspector Pointer - The Eames-Erskine Case (1/23) {ordered}

(1925 - 1961) ***John Rhode - Dr Priestley - Mystery At Greycombe Farm (12/72) {rare, expensive}

(1925 - 1953) *G. D. H. Cole / M. Cole - Superintendent Wilson - The Blatchington Tangle (3/?) {AbeBooks, expensive}

(1925 - 1937) *Hulbert Footner - Madame Storey - The Under Dogs (1/8) {ebookbrowse / Arthur's Bookshelf}

(1925 - 1932) *Earl Derr Biggers - Charlie Chan - The House Without A Key (1/6) {Internet Archive}

(1925 - 1944) *Agatha Christie - Superintendent Battle - Cards On The Table (3/5) {owned}

(1925 - 1934) *Anthony Berkeley - Roger Sheringham - The Layton Court Mystery (1/10) {Book Depository}

(1925 - 1950) *Anthony Wynne (Robert McNair Wilson) - Dr Eustace Hailey - The Mystery Of The Evil Eye (aka The Sign Of Evil) (1/27) {AbeBooks}

(1926 - 1968) * / ***Christopher Bush - Ludovic Travers - The Perfect Murder Case (2/63) {online}

(1926 - 1939) *S. S. Van Dine - Philo Vance - The Benson Murder Case (1/12) {Fisher Library}

(1926 - 1952) *J. Jefferson Farjeon - Ben the Tramp - No. 17 (1/8) {academic loan}

(1926 - ????) *G. D. H. Cole / M. Cole - Everard Blatchington - The Blatchington Tangle (1/?) {AbeBooks, expensive}

(1927 - 1933) *Herman Landon - The Picaroon - The Green Shadow (1/7) {AbeBooks / eBay}

(1927 - 1932) *Anthony Armstrong - Jimmie Rezaire - Jimmie Rezaire aka The Trail Of Fear (1/5) {AbeBooks}

(1927 - 1937) *Ronald Knox - Miles Bredon - The Three Taps (1/5) {AbeBooks}

(1927 - 1958) *Brian Flynn - Anthony Bathurst - The Billiard-Room Mystery (1/54) {AbeBooks}

(1927 - 1947) *J. J. Connington - Sir Clinton Driffield - Murder In The Maze (1/17) {academic loan}

(1927 - 1935) *Anthony Gilbert (Lucy Malleson) - Scott Egerton - Tragedy At Freyne (1/10) {expensive}

(1928 - 1961) Patricia Wentworth - Miss Silver - The Case Is Closed (2/33) {branch transfer}

(1928 - 1936) ***Gavin Holt - Luther Bastion - The Garden Of Silent Beasts (5/17) {academic loan}

(1928 - ????) Trygve Lund - Weston of the Royal North-West Mounted Police - In The Snow: A Romance Of The Canadian Backwoods (4/?) {AbeBooks}

(1928 - 1936) *Kay Cleaver Strahan - Lynn MacDonald - Death Traps (3/7) {AbeBooks}

(1928 - 1937) *John Alexander Ferguson - Francis McNab - Murder On The Marsh (2/5) {Internet Archive}

(1928 - 1960) *Cecil Freeman Gregg - Inspector Higgins - The Murdered Manservant (1/35) {unavailable}

(1928 - 1959) *John Gordon Brandon - Inspector Patrick Aloysius McCarthy - Red Altars (1/?) {AbeBooks}

(1928 - 1935) *Roland Daniel - Inspector Saville - The Society Of The Spiders (1/?) {Unavailable}

(1928 - 1946) *Francis Beeding - Alistair Granby - The Six Proud Walkers (1/18) {academic loan}

(1929 - 1947) Margery Allingham - Albert Campion - Sweet Danger (5/35) {Fisher Library}

(1929 - 1984) Gladys Mitchell - Mrs Bradley - The Saltmarsh Murders (4/67) {interlibrary loan}

(1929 - 1937) ***Patricia Wentworth - Benbow Smith - Walk With Care (3/4) {expensive}

(1929 - ????) Mignon Eberhart - Nurse Sarah Keate - Murder By An Aristocrat (5/8) {Better World Books}

(1929 - ????) Moray Dalton - Inspector Collier - ???? (3/?) - Death In The Cup {AbeBooks}, The Wife Of Baal {unavailable}

(1929 - ????) * / ***Charles Reed Jones - Leighton Swift - The King Murder (1/?) {Unavailable}

(1929 - 1931) Carolyn Wells - Kenneth Carlisle - Sleeping Dogs (1/3) {Amazon / eBay}

(1929 - 1967) *George Goodchild - Inspector McLean - McLean Of Scotland Yard (1/65) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - 1979) *Leonard Gribble - Anthony Slade - The Case Of The Marsden Rubies (1/33) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - 1932) *E. R. Punshon - Carter and Bell - The Unexpected Legacy (1/5) {expensive}

(1929 - 1971) *Ellery Queen - Ellery Queen - The Roman Hat Mystery (1/40) {interlibrary loan}

(1929 - 1966) *Arthur Upfield - Bony - The Barrakee Mystery (1/29) {Fisher Library}

(1929 - 1931) *Ernest Raymond - Once In England - A Family That Was (1/3) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - 1937) *Anthony Berkeley - Ambrose Chitterwick - The Poisoned Chocolates Case (1/3) {City of Sydney / Fisher Library}

(1929 - 1940) *Jean Lilly - DA Bruce Perkins - The Seven Sisters (1/3) {AbeBooks / expensive shipping}

(1929 - 1935) *N. A. Temple-Ellis (Nevile Holdaway) - Montrose Arbuthnot - The Inconsistent Villains (1/4) {AbeBooks / expensive shipping}

(1929 - 1943) *Gret Lane - Kate Clare Marsh and Inspector Barrin - The Cancelled Score Mystery (1/9) {unavailable?}

(1929 - 1961) *Henry Holt - Inspector Silver - The Mayfair Mystery (aka "The Mayfair Murder") (1/16) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - 1930) *J. J. Connington - Superintendent Ross - The Eye In The Museum (1/2) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - 1941) *H. Maynard Smith - Inspector Frost - Inspector Frost's Jigsaw (1/7) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - ????) *Armstrong Livingston - Jimmy Traynor - The Doublecross (1/?) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - ????) Moray Dalton - Hermann Glide - ???? (3/?) {see above}

(1930 - 1932) Hugh Walpole - The Herries Chronicles - The Fortress (3/4) {Fisher Library}

(1930 - 1932) Faith Baldwin - The Girls Of Divine Corners - Myra: A Story Of Divine Corners (4/4) {owned}

(1930 - 1960) ***Miles Burton - Desmond Merrion - The Milk-Churn Murder (10/61) {Munsey's}

(1930 - 1933) Roger Scarlett - Inspector Kane - Murder Among The Angells (4/5) {online shopping}

(1930 - 1941) *Harriette Ashbrook - Philip "Spike" Tracy - The Murder Of Sigurd Sharon (3/7) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - 1943) Anthony Abbot - Thatcher Colt - About The Murder Of The Night Club Lady (3/8) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - ????) * / ***David Sharp - Professor Henry Arthur Fielding - My Particular Murder (2/?) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - 1950) *H. C. Bailey - Josiah Clunk - Garstons aka The Garston Murder Case (1/11) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - 1968) *Francis Van Wyck Mason - Captain North - Seeds Of Murder (1/41) {rare, expensive}

(1930 - 1976) *Agatha Christie - Miss Jane Marple - The Body In The Library (2/12) {owned}

(1930 - ????) *Anne Austin - James "Bonnie" Dundee - Murder Backstairs (1/?) - {AbeBooks}

(1930 - 1950) *Leslie Ford (as David Frome) - Mr Pinkerton and Inspector Bull - The Hammersmith Murders (1/11) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - 1935) *"Diplomat" (John Franklin Carter) - Dennis Tyler - Murder In The State Department (1/7) {expensive}

(1930 - 1962) *Helen Reilly - Inspector Christopher McKee - The Diamond Feather (1/31) {AbeBooks / expensive shipping}

(1930 - 1933) *Mary Plum - John Smith - The Killing Of Judge MacFarlane (1/4) {AbeBooks}

(1931 - 1940) Bruce Graeme - Superintendent Stevens and Pierre Allain - The Imperfect Crime (2/8) {AbeBooks}

(1931 - 1951) Phoebe Atwood Taylor - Asey Mayo - Death Lights A Candle (2/24) {interlibrary loan}

(1931 - 1933) ***Martin Porlock - Charles Fox-Browne - Mystery In Kensington Gore (2/3) {unavailable}

(1931 - 1955) Stuart Palmer - Hildegarde Withers - Murder On Wheels (2/18) {AbeBooks}

(1931 - 1951) Olive Higgins Prouty - The Vale Novels - Lisa Vale (2/5) {academic loan}

(1931 - 1933) Sydney Fowler - Inspector Cleveland - Crime &. Co. (2/4) {owned}

(1931 - 1934) J. H. Wallis - Inspector Wilton Jacks - Murder By Formula (1/6) {Amazon}

(1931 - ????) Paul McGuire - Inspector Cummings - Daylight Murder (3/5) {academic loan}

(1931 - 1937) Carlton Dawe - Leathermouth - The Sign Of The Glove (2/13) {academic loan}

(1931 - 1947) R. L. Goldman - Asaph Clume and Rufus Reed - The Murder Of Harvey Blake (1/6) {AbeBooks}

(1931 - 1959) E. C. R. Lorac (Edith Caroline Rivett) - Inspector Robert Macdonald - The Murder On The Burrows (1/46) {rare, expensive}

(1931 - ????) Clifton Robbins - Clay Harrison - Dusty Death (1/?) {AbeBooks}

(1931 - 1972) Georges Simenon - Inspector Maigret - Pietr-le-Letton (1/75) {ordered}

(1931 - 1934) T. S. Stribling - The Vaiden Trilogy - The Forge (1/3) {academic loan}

(1932 - 1954) Sydney Fowler - Inspector Cambridge and Mr Jellipot - The Bell Street Murders (1/11) {AbeBooks}

(1932 - 1935) Murray Thomas - Inspector Wilkins - Buzzards Pick The Bones (1/3) {AbeBooks / expensive}

(1932 - ????) R. A. J. Walling - Philip Tolefree - The Fatal Five Minutes (1/?) {academic loan}

(1932 - 1962) T. Arthur Plummer - Detective-Inspector Andrew Frampton - Shadowed By The C. I. D. (1/50) {unavailable?}

(1932 - 1936) John Victor Turner - Amos Petrie - Death Must Have Laughed (1/7) {unavailable?}

(1932 - 1944) Nicholas Brady (John Victor Turner) - Ebenezer Buckle - The House Of Strange Guests (1/4) {unavailable?}

(1933 - 1959) John Gordon Brandon - Arthur Stukeley Pennington - West End! (1/?) {AbeBooks}

(1933 - 1940) Lilian Garis - Carol Duncan - The Ghost Of Melody Lane (1/9) {AbeBooks}

(1933 - 1934) Peter Hunt (George Worthing Yates and Charles Hunt Marshall) - Allan Miller - Murders At Scandal House (1/3) {AbeBooks / Amazon}

(1933 - 1968) John Dickson Carr - Gideon Fell - Hag's Nook (1/23) {Better World Books}

(1933 - 1939) Gregory Dean - Deputy Commissioner Benjamin Simon - The Case Of Marie Corwin (1/3) {AbeBooks / Amazon}

(1933 - 1956) E. R. Punshon - Detective-Sergeant Bobby Owen - Information Received (1/35) {academic loan}

(1933 - 1970) Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richlieu - The Forbidden Territory (1/11) {Fisher Library}

(1934 - 1936) Storm Jameson - The Mirror In Darkness - Company Parade (1/3) {Fisher Library}

(1934 - 1953) Leslie Ford (Zenith Jones Brown) - Colonel John Primrose and Grace Latham - The Clock Strikes Twelve (aka "The Supreme Court Murder") (NB: novella)

(1934 - 1949) Richard Goyne - Paul Templeton - Strange Motives (1/13) {unavailable?}

(1934 - 1941) N. A. Temple-Ellis (Nevile Holdaway) - Inspector Wren - Three Went In (1/3)

(1934 - 1953) Carter Dickson (John Dickson Carr) - Sir Henry Merivale - The Plague Court Murders (1/22) {Fisher Library}

(1934 - 1968) Dennis Wheatley - Gregory Sallust - Black August (1/11)

(1935 - 1939) Francis Beeding - Inspector George Martin - The Norwich Victims (1/3) {AbeBooks / Book Depository}

(1935 - 1976) Nigel Morland - Palmyra Pym - The Moon Murders (1/28) {unavailable?}

(1935 - 1941) Clyde Clason - Professor Theocritus Lucius Westborough - The Fifth Tumbler (1/10) {unavailable?}

(1935 - ????) G. D. H. Cole / M. Cole - Dr Tancred - Dr Tancred Begins (1/?) (AbeBooks, expensive}

(1947 - 1974) Dennis Wheatley - Roger Brook - The Launching Of Roger Brook (1/12) {Fisher Library storage}

(1953 - 1960) Dennis Whealey - Molly Fountain and Colonel Verney - To The Devil A Daughter (1/2) {Fisher Library storage}

*** Incompletely available series

** Series complete pre-1931

* Present status pre-1931

(1866 - 1876) **Emile Gaboriau - Monsieur Lecoq - The Widow Lerouge (1/6) {ManyBooks}

(1867 - 1905) **Martha Finley - Elsie Dinsmore - Holidays At Roselands (2/28) {ManyBooks}

(1878 - 1917) **Anna Katharine Green - Ebenezer Gryce - Behind Closed Doors (5/12) {Book Depository}

(1894 - 1898) **Anthony Hope - Ruritania - The Heart Of Princess Osra (2/3) {Project Gutenberg}

(1895 - 1901) **Guy Newell Boothby - Dr Nikola - A Bid For Fortune (1/5) {Project Gutenberg}

(1897 - 1900) **Anna Katharine Green - Amelia Butterworth - That Affair Next Door (1/3) {Fisher Library}

(1900 - 1974) *Ernest Bramah - Kai Lung - The Wallet Of Kai Lung (1/6) {ManyBooks}

(1901 - 1919) **Carolyn Wells - Patty Fairfield - Patty's Summer Days (4/17) {ManyBooks}

(1903 - 1904) **Louis Tracy - Reginald Brett - A Fatal Legacy (aka The Stowmarket Mystery) (1/2) {ManyBooks}

(1904 - ????) *Louis Tracy - Winter and Furneaux - The Albert Gate Mystery (1/?) {ManyBooks}

(1905 - 1928) **Edgar Wallace - The Just Men - The Just Men Of Cordova (3/6) {ManyBooks}

(1906 - 1930) **John Galsworthy - The Forsyte Saga - The Man Of Property (1/11) {Fisher Library}

(1907 - 1912) **Carolyn Wells - Marjorie - Marjorie's Vacation (1/6) {ManyBooks}

(1907 - 1942) *R. Austin Freeman - Dr John Thorndyke - The D'Arblay Mystery (13/26) {Feedbooks}

(1907 - 1941) *Maurice Leblanc - Arsene Lupin - Arsene Lupin, Gentleman Burglar (1/21) {ManyBooks}

(1908 - 1924) **Margaret Penrose - Dorothy Dale - Dorothy Dale: A Girl Of Today (1/13) {ManyBooks}

(1909 - 1942) *Carolyn Wells - Fleming Stone - Raspberry Jam (11/49) {ManyBooks}

(1910 - 1936) *Arthur B. Reeve - Craig Kennedy - The Social Gangster (5/11) {ManyBooks}

(1910 - 1946) A. E. W. Mason - Inspector Hanaud - They Wouldn't Be Chessmen (4/5) {AbeBooks}

(1910 - ????) *Edgar Wallace - Inspector Smith - Kate Plus Ten (3/?) {Project Gutenberg Australia}

(1910 - 1930) **Edgar Wallace - Inspector Elk - The Fellowship Of The Frog (2/6?) {ebook}

(1910 - ????) *Thomas Hanshew - Cleek - Cleek's Government Cases (3/?) {Internet Archive / Mobilereads}

(1910 - 1918) *John McIntyre - Ashton-Kirk - Ashton-Kirk: Investigator (1/4) {ManyBooks / Project Gutenberg}

(1910 - 1931) *Grace S. Richmond - Red Pepper Burns - Red Pepper Burns (1/6) {ManyBooks}

(1911 - 1937) *Mary Roberts Rinehart - Letitia Carberry - Tish Plays The Game (4/5) {GooglePlay}

(1913 - 1934) *Alice B. Emerson - Ruth Fielding - Ruth Fielding At Sunrise Farm (7/30) {Project Gutenberg}

(1913 - 1973) Sax Rohmer - Fu-Manchu - The Mask Of Fu-Manchu (5/14) {interlibrary loan}

(1914 - 1950) Mary Roberts Rinehart - Hilda Adams - Haunted Lady (4/5) {Owned}

(1914 - 1934) *Ernest Bramah - Max Carrados - The Eyes Of Max Carrados (2/4) {interlibrary loan}

(1916 - 1917) **Carolyn Wells - Alan Ford - Faulkner's Folly (2/2) {Book Depository}

(1918 - 1923) **Carolyn Wells - Pennington Wise - The Room With The Tassels (1/8) {Internet Archive / Book Depository}

(1919 - 1966) *Lee Thayer - Peter Clancy - The Sinister Mark (5/60) {owned}

(1920 - 1939) E. F. Benson - Mapp And Lucia - Lucia's Progress (5/6) {Fisher Library}

(1920 - 1948) *H. C. Bailey - Reggie Fortune - Mr Fortune, Please (4/23) {academic loan}

(1920 - 1949) William McFee - Spenlove - The Beachcomber - (3/6) {AbeBooks}

(1920 - 1932) *Alice B. Emerson - Betty Gordon - Betty Gordon At Bramble Farm (1/15) {ManyBooks}

(1920 - 1975) *Agatha Christie - Hercule Poirot - Peril At End House (7/39) {owned}

(1921 - 1929) **Charles J. Dutton - John Bartley - The Second Bullet (5/9) {expensive}

(1921 - 1925) **Herman Landon - The Gray Phantom - The Gray Phantom's Return (2/5) {Project Gutenberg}

(1922 - 1973) *Agatha Christie - Tommy and Tuppence - N. Or M.? (3/5) {owned}

(1922 - 1927) *Alice MacGowan and Perry Newberry - Jerry Boyne - The Mystery Woman (2/5) {Amazon, eBay?}

(1923 - 1937) Dorothy L. Sayers - Lord Peter Wimsey - Have His Carcase (8/15) {Fisher Library}

(1923 - 1924) **Carolyn Wells - Lorimer Lane - The Fourteenth Key (2/2) {Amazon domestic}

(1924 - 1959) * / ***Philip MacDonald - Colonel Anthony Gethryn - Persons Unknown (aka "The Maze") (5/24) {academic loan}

(1924 - 1957) *Freeman Wills Crofts - Inspector French - The Cheyne Mystery (2/30) {Fisher Library}

(1924 - 1935) *Francis D. Grierson - Inspector Sims and Professor Wells - The Limping Man (1/13) {owned}

(1924 - 1940) *Lynn Brock - Colonel Gore - The Deductions Of Colonel Gore (1/12) {owned}

(1924 - 1933) *Herbert Adams - Jimmie Haswell - The Secret Of Bogey House (1/9) {owned}

(1924 - 1944) *A. Fielding - Inspector Pointer - The Eames-Erskine Case (1/23) {ordered}

(1925 - 1961) ***John Rhode - Dr Priestley - Mystery At Greycombe Farm (12/72) {rare, expensive}

(1925 - 1953) *G. D. H. Cole / M. Cole - Superintendent Wilson - The Blatchington Tangle (3/?) {AbeBooks, expensive}

(1925 - 1937) *Hulbert Footner - Madame Storey - The Under Dogs (1/8) {ebookbrowse / Arthur's Bookshelf}

(1925 - 1932) *Earl Derr Biggers - Charlie Chan - The House Without A Key (1/6) {Internet Archive}

(1925 - 1944) *Agatha Christie - Superintendent Battle - Cards On The Table (3/5) {owned}

(1925 - 1934) *Anthony Berkeley - Roger Sheringham - The Layton Court Mystery (1/10) {Book Depository}

(1925 - 1950) *Anthony Wynne (Robert McNair Wilson) - Dr Eustace Hailey - The Mystery Of The Evil Eye (aka The Sign Of Evil) (1/27) {AbeBooks}

(1926 - 1968) * / ***Christopher Bush - Ludovic Travers - The Perfect Murder Case (2/63) {online}

(1926 - 1939) *S. S. Van Dine - Philo Vance - The Benson Murder Case (1/12) {Fisher Library}

(1926 - 1952) *J. Jefferson Farjeon - Ben the Tramp - No. 17 (1/8) {academic loan}

(1926 - ????) *G. D. H. Cole / M. Cole - Everard Blatchington - The Blatchington Tangle (1/?) {AbeBooks, expensive}

(1927 - 1933) *Herman Landon - The Picaroon - The Green Shadow (1/7) {AbeBooks / eBay}

(1927 - 1932) *Anthony Armstrong - Jimmie Rezaire - Jimmie Rezaire aka The Trail Of Fear (1/5) {AbeBooks}

(1927 - 1937) *Ronald Knox - Miles Bredon - The Three Taps (1/5) {AbeBooks}

(1927 - 1958) *Brian Flynn - Anthony Bathurst - The Billiard-Room Mystery (1/54) {AbeBooks}

(1927 - 1947) *J. J. Connington - Sir Clinton Driffield - Murder In The Maze (1/17) {academic loan}

(1927 - 1935) *Anthony Gilbert (Lucy Malleson) - Scott Egerton - Tragedy At Freyne (1/10) {expensive}

(1928 - 1961) Patricia Wentworth - Miss Silver - The Case Is Closed (2/33) {branch transfer}

(1928 - 1936) ***Gavin Holt - Luther Bastion - The Garden Of Silent Beasts (5/17) {academic loan}

(1928 - ????) Trygve Lund - Weston of the Royal North-West Mounted Police - In The Snow: A Romance Of The Canadian Backwoods (4/?) {AbeBooks}

(1928 - 1936) *Kay Cleaver Strahan - Lynn MacDonald - Death Traps (3/7) {AbeBooks}

(1928 - 1937) *John Alexander Ferguson - Francis McNab - Murder On The Marsh (2/5) {Internet Archive}

(1928 - 1960) *Cecil Freeman Gregg - Inspector Higgins - The Murdered Manservant (1/35) {unavailable}

(1928 - 1959) *John Gordon Brandon - Inspector Patrick Aloysius McCarthy - Red Altars (1/?) {AbeBooks}

(1928 - 1935) *Roland Daniel - Inspector Saville - The Society Of The Spiders (1/?) {Unavailable}

(1928 - 1946) *Francis Beeding - Alistair Granby - The Six Proud Walkers (1/18) {academic loan}

(1929 - 1947) Margery Allingham - Albert Campion - Sweet Danger (5/35) {Fisher Library}

(1929 - 1984) Gladys Mitchell - Mrs Bradley - The Saltmarsh Murders (4/67) {interlibrary loan}

(1929 - 1937) ***Patricia Wentworth - Benbow Smith - Walk With Care (3/4) {expensive}

(1929 - ????) Mignon Eberhart - Nurse Sarah Keate - Murder By An Aristocrat (5/8) {Better World Books}

(1929 - ????) Moray Dalton - Inspector Collier - ???? (3/?) - Death In The Cup {AbeBooks}, The Wife Of Baal {unavailable}

(1929 - ????) * / ***Charles Reed Jones - Leighton Swift - The King Murder (1/?) {Unavailable}

(1929 - 1931) Carolyn Wells - Kenneth Carlisle - Sleeping Dogs (1/3) {Amazon / eBay}

(1929 - 1967) *George Goodchild - Inspector McLean - McLean Of Scotland Yard (1/65) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - 1979) *Leonard Gribble - Anthony Slade - The Case Of The Marsden Rubies (1/33) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - 1932) *E. R. Punshon - Carter and Bell - The Unexpected Legacy (1/5) {expensive}

(1929 - 1971) *Ellery Queen - Ellery Queen - The Roman Hat Mystery (1/40) {interlibrary loan}

(1929 - 1966) *Arthur Upfield - Bony - The Barrakee Mystery (1/29) {Fisher Library}

(1929 - 1931) *Ernest Raymond - Once In England - A Family That Was (1/3) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - 1937) *Anthony Berkeley - Ambrose Chitterwick - The Poisoned Chocolates Case (1/3) {City of Sydney / Fisher Library}

(1929 - 1940) *Jean Lilly - DA Bruce Perkins - The Seven Sisters (1/3) {AbeBooks / expensive shipping}

(1929 - 1935) *N. A. Temple-Ellis (Nevile Holdaway) - Montrose Arbuthnot - The Inconsistent Villains (1/4) {AbeBooks / expensive shipping}

(1929 - 1943) *Gret Lane - Kate Clare Marsh and Inspector Barrin - The Cancelled Score Mystery (1/9) {unavailable?}

(1929 - 1961) *Henry Holt - Inspector Silver - The Mayfair Mystery (aka "The Mayfair Murder") (1/16) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - 1930) *J. J. Connington - Superintendent Ross - The Eye In The Museum (1/2) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - 1941) *H. Maynard Smith - Inspector Frost - Inspector Frost's Jigsaw (1/7) {AbeBooks}

(1929 - ????) *Armstrong Livingston - Jimmy Traynor - The Doublecross (1/?) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - ????) Moray Dalton - Hermann Glide - ???? (3/?) {see above}

(1930 - 1932) Hugh Walpole - The Herries Chronicles - The Fortress (3/4) {Fisher Library}

(1930 - 1932) Faith Baldwin - The Girls Of Divine Corners - Myra: A Story Of Divine Corners (4/4) {owned}

(1930 - 1960) ***Miles Burton - Desmond Merrion - The Milk-Churn Murder (10/61) {Munsey's}

(1930 - 1933) Roger Scarlett - Inspector Kane - Murder Among The Angells (4/5) {online shopping}

(1930 - 1941) *Harriette Ashbrook - Philip "Spike" Tracy - The Murder Of Sigurd Sharon (3/7) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - 1943) Anthony Abbot - Thatcher Colt - About The Murder Of The Night Club Lady (3/8) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - ????) * / ***David Sharp - Professor Henry Arthur Fielding - My Particular Murder (2/?) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - 1950) *H. C. Bailey - Josiah Clunk - Garstons aka The Garston Murder Case (1/11) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - 1968) *Francis Van Wyck Mason - Captain North - Seeds Of Murder (1/41) {rare, expensive}

(1930 - 1976) *Agatha Christie - Miss Jane Marple - The Body In The Library (2/12) {owned}

(1930 - ????) *Anne Austin - James "Bonnie" Dundee - Murder Backstairs (1/?) - {AbeBooks}

(1930 - 1950) *Leslie Ford (as David Frome) - Mr Pinkerton and Inspector Bull - The Hammersmith Murders (1/11) {AbeBooks}

(1930 - 1935) *"Diplomat" (John Franklin Carter) - Dennis Tyler - Murder In The State Department (1/7) {expensive}

(1930 - 1962) *Helen Reilly - Inspector Christopher McKee - The Diamond Feather (1/31) {AbeBooks / expensive shipping}

(1930 - 1933) *Mary Plum - John Smith - The Killing Of Judge MacFarlane (1/4) {AbeBooks}

(1931 - 1940) Bruce Graeme - Superintendent Stevens and Pierre Allain - The Imperfect Crime (2/8) {AbeBooks}

(1931 - 1951) Phoebe Atwood Taylor - Asey Mayo - Death Lights A Candle (2/24) {interlibrary loan}

(1931 - 1933) ***Martin Porlock - Charles Fox-Browne - Mystery In Kensington Gore (2/3) {unavailable}

(1931 - 1955) Stuart Palmer - Hildegarde Withers - Murder On Wheels (2/18) {AbeBooks}

(1931 - 1951) Olive Higgins Prouty - The Vale Novels - Lisa Vale (2/5) {academic loan}

(1931 - 1933) Sydney Fowler - Inspector Cleveland - Crime &. Co. (2/4) {owned}

(1931 - 1934) J. H. Wallis - Inspector Wilton Jacks - Murder By Formula (1/6) {Amazon}

(1931 - ????) Paul McGuire - Inspector Cummings - Daylight Murder (3/5) {academic loan}

(1931 - 1937) Carlton Dawe - Leathermouth - The Sign Of The Glove (2/13) {academic loan}

(1931 - 1947) R. L. Goldman - Asaph Clume and Rufus Reed - The Murder Of Harvey Blake (1/6) {AbeBooks}

(1931 - 1959) E. C. R. Lorac (Edith Caroline Rivett) - Inspector Robert Macdonald - The Murder On The Burrows (1/46) {rare, expensive}

(1931 - ????) Clifton Robbins - Clay Harrison - Dusty Death (1/?) {AbeBooks}

(1931 - 1972) Georges Simenon - Inspector Maigret - Pietr-le-Letton (1/75) {ordered}

(1931 - 1934) T. S. Stribling - The Vaiden Trilogy - The Forge (1/3) {academic loan}

(1932 - 1954) Sydney Fowler - Inspector Cambridge and Mr Jellipot - The Bell Street Murders (1/11) {AbeBooks}

(1932 - 1935) Murray Thomas - Inspector Wilkins - Buzzards Pick The Bones (1/3) {AbeBooks / expensive}

(1932 - ????) R. A. J. Walling - Philip Tolefree - The Fatal Five Minutes (1/?) {academic loan}

(1932 - 1962) T. Arthur Plummer - Detective-Inspector Andrew Frampton - Shadowed By The C. I. D. (1/50) {unavailable?}

(1932 - 1936) John Victor Turner - Amos Petrie - Death Must Have Laughed (1/7) {unavailable?}

(1932 - 1944) Nicholas Brady (John Victor Turner) - Ebenezer Buckle - The House Of Strange Guests (1/4) {unavailable?}

(1933 - 1959) John Gordon Brandon - Arthur Stukeley Pennington - West End! (1/?) {AbeBooks}

(1933 - 1940) Lilian Garis - Carol Duncan - The Ghost Of Melody Lane (1/9) {AbeBooks}

(1933 - 1934) Peter Hunt (George Worthing Yates and Charles Hunt Marshall) - Allan Miller - Murders At Scandal House (1/3) {AbeBooks / Amazon}

(1933 - 1968) John Dickson Carr - Gideon Fell - Hag's Nook (1/23) {Better World Books}

(1933 - 1939) Gregory Dean - Deputy Commissioner Benjamin Simon - The Case Of Marie Corwin (1/3) {AbeBooks / Amazon}

(1933 - 1956) E. R. Punshon - Detective-Sergeant Bobby Owen - Information Received (1/35) {academic loan}

(1933 - 1970) Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richlieu - The Forbidden Territory (1/11) {Fisher Library}

(1934 - 1936) Storm Jameson - The Mirror In Darkness - Company Parade (1/3) {Fisher Library}

(1934 - 1953) Leslie Ford (Zenith Jones Brown) - Colonel John Primrose and Grace Latham - The Clock Strikes Twelve (aka "The Supreme Court Murder") (NB: novella)

(1934 - 1949) Richard Goyne - Paul Templeton - Strange Motives (1/13) {unavailable?}

(1934 - 1941) N. A. Temple-Ellis (Nevile Holdaway) - Inspector Wren - Three Went In (1/3)

(1934 - 1953) Carter Dickson (John Dickson Carr) - Sir Henry Merivale - The Plague Court Murders (1/22) {Fisher Library}

(1934 - 1968) Dennis Wheatley - Gregory Sallust - Black August (1/11)

(1935 - 1939) Francis Beeding - Inspector George Martin - The Norwich Victims (1/3) {AbeBooks / Book Depository}

(1935 - 1976) Nigel Morland - Palmyra Pym - The Moon Murders (1/28) {unavailable?}

(1935 - 1941) Clyde Clason - Professor Theocritus Lucius Westborough - The Fifth Tumbler (1/10) {unavailable?}

(1935 - ????) G. D. H. Cole / M. Cole - Dr Tancred - Dr Tancred Begins (1/?) (AbeBooks, expensive}

(1947 - 1974) Dennis Wheatley - Roger Brook - The Launching Of Roger Brook (1/12) {Fisher Library storage}

(1953 - 1960) Dennis Whealey - Molly Fountain and Colonel Verney - To The Devil A Daughter (1/2) {Fisher Library storage}

*** Incompletely available series

** Series complete pre-1931

* Present status pre-1931

7lyzard

Timeline of detective fiction:

Pre-history:

Things As They Are; or, The Adventures Of Caleb Williams by William Godwin (1794)

Mademoiselle de Scudéri by E.T.A. Hoffmann (1819)

Richmond: Scenes In The Life Of A Bow Street Officer by Anonymous (1827)

Memoirs Of Vidocq by Eugene Francois Vidocq (1828)

Le Pere Goriot by Honore de Balzac (1835)

Passages In The Secret History Of An Irish Countess by J. Sheridan Le Fanu (1838); The Purcell Papers (1880)

The Murders In The Rue Morgue: The Dupin Tales by Edgar Allan Poe {interlibrary loan} (1841, 1842, 1845)

Serials:

The Mysteries Of Paris by Eugene Sue (1842 - 1843)

The Mysteries Of London - Paul Feval (1844) (no translation?)

The Mysteries Of London - George Reynolds (1844 - 1848)

The Mysteries Of The Court Of London - George Reynolds (1848 - 1856)

John Devil by Paul Feval (1861)

Early detective novels:

Recollections Of A Detective Police-Officer by "Waters" (William Russell) (1856)

The Widow Lerouge by Emile Gaboriau (1866)

Under Lock And Key by T. W. Speight (1869)

Checkmate by J. Sheridan LeFanu (1871)

Is He The Man? by William Clark Russell (1876)

Devlin The Barber by B. J. Farjeon (1888)

Mr Meeson's Will by H. Rider Haggard (1888)

The Mystery Of A Hansom Cab by Fergus Hume (1889)

The Queen Anne's Gate Mystery by Richard Arkwright (1889)

The Ivory Queen by Norman Hurst (1889) (Check Julius H. Hurst 1899)

The Big Bow Mystery by Israel Zangwill (1892)

Female detectives:

The Diary Of Anne Rodway by Wilkie Collins (1856)

The Female Detective by Andrew Forrester (1864)

Revelations Of A Lady Detective by William Stephens Hayward (1864)

Madeline Payne; or, The Detective's Daughter by Lawrence L. Lynch (Emma Murdoch Van Deventer) (1884)

Mr Bazalgette's Agent by Leonard Merrick (1888)

Moina; or, Against The Mighty by Lawrence L. Lynch (Emma Murdoch Van Deventer) (sequel to Madeline Payne?) (1891)

The Experiences Of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective by Catherine Louisa Pirkis (1893)

Dorcas Dene, Detective by George Sims (1897)

- Amelia Butterworth series by Anna Katharine Grant (1897 - 1900)

Miss Cayley's Adventures by Grant Allan (1899)

Hilda Wade by Grant Allan (1900)

Dora Myrl, The Lady Detective by M. McDonnel Bodkin (1900)

Lady Molly Of Scotland Yard by Baroness Orczy (1910)

Related mainstream works:

Adventures Of Susan Hopley by Catherine Crowe (1841)

Men And Women; or, Manorial Rights by Catherine Crowe (1843)

Hargrave by Frances Trollope (1843)

Clement Lorimer by Angus Reach (1849)

True crime:

Clues: or, Leaves from a Chief Constable's Note Book by Sir William Henderson (1889)

Dreadful Deeds And Awful Murders by Joan Lock

Pre-history:

Serials:

The Mysteries Of Paris by Eugene Sue (1842 - 1843)

The Mysteries Of London - Paul Feval (1844) (no translation?)

The Mysteries Of London - George Reynolds (1844 - 1848)

The Mysteries Of The Court Of London - George Reynolds (1848 - 1856)

John Devil by Paul Feval (1861)

Early detective novels:

Recollections Of A Detective Police-Officer by "Waters" (William Russell) (1856)

The Widow Lerouge by Emile Gaboriau (1866)

Under Lock And Key by T. W. Speight (1869)

Checkmate by J. Sheridan LeFanu (1871)

Is He The Man? by William Clark Russell (1876)

Devlin The Barber by B. J. Farjeon (1888)

Mr Meeson's Will by H. Rider Haggard (1888)

The Mystery Of A Hansom Cab by Fergus Hume (1889)

The Queen Anne's Gate Mystery by Richard Arkwright (1889)

The Ivory Queen by Norman Hurst (1889) (Check Julius H. Hurst 1899)

The Big Bow Mystery by Israel Zangwill (1892)

Female detectives:

The Diary Of Anne Rodway by Wilkie Collins (1856)

The Female Detective by Andrew Forrester (1864)

Revelations Of A Lady Detective by William Stephens Hayward (1864)

Madeline Payne; or, The Detective's Daughter by Lawrence L. Lynch (Emma Murdoch Van Deventer) (1884)

Mr Bazalgette's Agent by Leonard Merrick (1888)

Moina; or, Against The Mighty by Lawrence L. Lynch (Emma Murdoch Van Deventer) (sequel to Madeline Payne?) (1891)

The Experiences Of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective by Catherine Louisa Pirkis (1893)

Dorcas Dene, Detective by George Sims (1897)

- Amelia Butterworth series by Anna Katharine Grant (1897 - 1900)

Miss Cayley's Adventures by Grant Allan (1899)

Hilda Wade by Grant Allan (1900)

Dora Myrl, The Lady Detective by M. McDonnel Bodkin (1900)

Lady Molly Of Scotland Yard by Baroness Orczy (1910)

Related mainstream works:

Men And Women; or, Manorial Rights by Catherine Crowe (1843)

Hargrave by Frances Trollope (1843)

Clement Lorimer by Angus Reach (1849)

True crime:

Clues: or, Leaves from a Chief Constable's Note Book by Sir William Henderson (1889)

Dreadful Deeds And Awful Murders by Joan Lock

8lyzard

2013 stats:

Books read: 151

Oldest work: A True Relation Of A Horrid Murder Committed upon the Person of Thomas Kidderminster of Tupsley in the County of Hereford, Gent. by Anonymous (1688)

Newest work: Detective Piggott's Casebook: True Tales Of Murder, Madness And The Rise Of Forensic Science by Kevin John Morgan (2012), Women Writing Crime Fiction, 1860-1880: Fourteen American, British And Australian Authors by Kate Watson (2012)

Male authors: 77 (50.6%)

Female authors: 72 (47.4%)

Anonymous: 3 (2.0%)

New-to-me authors: 62 (40.8%)

Re-reads: 25 (16.6%)

Series reads: 62 (41.1%)

TIOLI: 146 (96.7%)

1931: 37 (24.5%)

Mysteries / thrillers: 70.5 (46.7%)

Classics*: 19 (12.6%)

Contemporary drama: 13 (8.6%)

Historical romance: 13 (8.6%)

Non-fiction: 11 (7.3%)

Young adult: 7 (4.6%)

Memoirs: 5.5 (3.6%)

Humour: 4 (2.6%)

Science fiction: 4 (2.6%)

Romance: 2 (1.4%)

Adventure: 1 (0.7%)

Fantasy: 1 (0.7%)

(*Anything published before 1900 not classified as mystery / thriller / adventure / science fiction / memoir)

Best in class (for categories >10 Ameise1: books read):

Mysteries / thrillers:

Hand And Ring: The Story Of A Mysterious Crime by Anna Katharine Green (1883)

The Man Of Last Resort; or, The Clients Of Randolph Mason by Melville Davisson Post (1897)

Vicky Van by Carolyn Wells (1918)

The Shadow Of The Wolf by R. Austin Freeman (1925)

*The Murder Of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie (1926)

The Incredulity Of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton (1926)

Footprints by Kay Cleaver Strahan (1929)

From This Dark Stairway by Mignon Eberhart (1931)

The Missing Money-Lender by W. Stanley Sykes (1931)

Murder Incidental by Keith Trask (1931)

Three Dead Men by Paul McGuire (1931)

The Detectives' Album: Stories Of Crime And Mystery From Colonial Australia by Mary Fortune (2003)

Classics:

*Things As They Are; or, The Adventures Of Caleb Williams by William Godwin (1794)

Le Père Goriot by Honore de Balzac (translated by Burton Raffel) (1835)

Adventures Of Susan Hopley; or, Circumstantial Evidence by Catharine Crowe (1841)

*Framley Parsonage by Anthony Trollope (1861)

*Can You Forgive Her? by Anthony Trollope (1865)

Historical romance:

Captain Blood by Rafael Sabatini (1922)

*The Masqueraders by Georgette Heyer (1928)

The True Heart by Sylvia Townsend Warner (1929)

Dragonwyck by Anya Seton (1944)

Non-fiction:

Silver Fork Society: Fashionable Life And Literature From 1814-1840 by Alison Adburgham (1983)

'Lesser Breeds': Racial Attitudes In Popular British Culture, 1890-1940 by Michael Diamond (2006)

The Invention Of Murder: How The Victorians Revelled In Death And Detection And Created Modern Crime by Judith Flanders (2011)

Women Writing Crime Fiction, 1860-1880: Fourteen American, British And Australian Authors by Kate Watson (2012)

Contemporary drama:

Painted Clay by Capel Boake (1917)

Friends And Relations by Elizabeth Bowen (1931)

Good fun:

Castle Of Wolfenbach: A German Story by Eliza Parsons (1793)

The Four Just Men by Edgar Wallace (1905)

The Man Of The Forty Faces by Thomas W. Hanshew (1910)

*The Secret Of Chimneys by Agatha Christie (1925)

Crime & Co. by Sydney Fowler (1931)

70,000 Witnesses by Cortland Fitzsimmons (1931)

Devil's Cub by Georgette Heyer (1932)

Ew!

The Court Secret by Peter Belon (1689)

Elsie Dinsmore by Martha Finley (1867)

The Sign Of The Spider by Bertram Mitford (1897)

The Devil Doctor by Sax Rohmer (Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward) (1916)

Leathermouth by Carlton Dawe (1931)

Lovers Of Janine by Denise Robins (1931)

The Reckoning by Joan Conquest (1931)

*/**Sanctuary by William Faulkner (1931)

The Singular Anomaly: Women Novelists Of The Nineteenth Century by Vineta Colby (1970)

Discoveries:

Catharine Crowe

Mary Helena Fortune

Thomas W. Hanshew

Paul McGuire

Rosa Praed

W. Stanley Sykes

*Re-read

**Part of me feels I owe Faulkner an apology for putting him in this company; the other part of me feels he had it coming.

Books read: 151

Oldest work: A True Relation Of A Horrid Murder Committed upon the Person of Thomas Kidderminster of Tupsley in the County of Hereford, Gent. by Anonymous (1688)

Newest work: Detective Piggott's Casebook: True Tales Of Murder, Madness And The Rise Of Forensic Science by Kevin John Morgan (2012), Women Writing Crime Fiction, 1860-1880: Fourteen American, British And Australian Authors by Kate Watson (2012)

Male authors: 77 (50.6%)

Female authors: 72 (47.4%)

Anonymous: 3 (2.0%)

New-to-me authors: 62 (40.8%)

Re-reads: 25 (16.6%)

Series reads: 62 (41.1%)

TIOLI: 146 (96.7%)

1931: 37 (24.5%)

Mysteries / thrillers: 70.5 (46.7%)

Classics*: 19 (12.6%)

Contemporary drama: 13 (8.6%)

Historical romance: 13 (8.6%)

Non-fiction: 11 (7.3%)

Young adult: 7 (4.6%)

Memoirs: 5.5 (3.6%)

Humour: 4 (2.6%)

Science fiction: 4 (2.6%)

Romance: 2 (1.4%)

Adventure: 1 (0.7%)

Fantasy: 1 (0.7%)

(*Anything published before 1900 not classified as mystery / thriller / adventure / science fiction / memoir)

Best in class (for categories >10 Ameise1: books read):

Mysteries / thrillers:

Hand And Ring: The Story Of A Mysterious Crime by Anna Katharine Green (1883)

The Man Of Last Resort; or, The Clients Of Randolph Mason by Melville Davisson Post (1897)

Vicky Van by Carolyn Wells (1918)

The Shadow Of The Wolf by R. Austin Freeman (1925)

*The Murder Of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie (1926)

The Incredulity Of Father Brown by G. K. Chesterton (1926)

Footprints by Kay Cleaver Strahan (1929)

From This Dark Stairway by Mignon Eberhart (1931)

The Missing Money-Lender by W. Stanley Sykes (1931)

Murder Incidental by Keith Trask (1931)

Three Dead Men by Paul McGuire (1931)

The Detectives' Album: Stories Of Crime And Mystery From Colonial Australia by Mary Fortune (2003)

Classics:

*Things As They Are; or, The Adventures Of Caleb Williams by William Godwin (1794)

Le Père Goriot by Honore de Balzac (translated by Burton Raffel) (1835)

Adventures Of Susan Hopley; or, Circumstantial Evidence by Catharine Crowe (1841)

*Framley Parsonage by Anthony Trollope (1861)

*Can You Forgive Her? by Anthony Trollope (1865)

Historical romance:

Captain Blood by Rafael Sabatini (1922)

*The Masqueraders by Georgette Heyer (1928)

The True Heart by Sylvia Townsend Warner (1929)

Dragonwyck by Anya Seton (1944)

Non-fiction:

Silver Fork Society: Fashionable Life And Literature From 1814-1840 by Alison Adburgham (1983)

'Lesser Breeds': Racial Attitudes In Popular British Culture, 1890-1940 by Michael Diamond (2006)

The Invention Of Murder: How The Victorians Revelled In Death And Detection And Created Modern Crime by Judith Flanders (2011)

Women Writing Crime Fiction, 1860-1880: Fourteen American, British And Australian Authors by Kate Watson (2012)

Contemporary drama:

Painted Clay by Capel Boake (1917)

Friends And Relations by Elizabeth Bowen (1931)

Good fun:

Castle Of Wolfenbach: A German Story by Eliza Parsons (1793)

The Four Just Men by Edgar Wallace (1905)

The Man Of The Forty Faces by Thomas W. Hanshew (1910)

*The Secret Of Chimneys by Agatha Christie (1925)

Crime & Co. by Sydney Fowler (1931)

70,000 Witnesses by Cortland Fitzsimmons (1931)

Devil's Cub by Georgette Heyer (1932)

Ew!

The Court Secret by Peter Belon (1689)

Elsie Dinsmore by Martha Finley (1867)

The Sign Of The Spider by Bertram Mitford (1897)

The Devil Doctor by Sax Rohmer (Arthur Henry Sarsfield Ward) (1916)

Leathermouth by Carlton Dawe (1931)

Lovers Of Janine by Denise Robins (1931)

The Reckoning by Joan Conquest (1931)

*/**Sanctuary by William Faulkner (1931)

The Singular Anomaly: Women Novelists Of The Nineteenth Century by Vineta Colby (1970)

Discoveries:

Catharine Crowe

Mary Helena Fortune

Thomas W. Hanshew

Paul McGuire

Rosa Praed

W. Stanley Sykes

*Re-read

**Part of me feels I owe Faulkner an apology for putting him in this company; the other part of me feels he had it coming.

9lyzard

Group reads, tutored reads, everybody's-welcome reads:

Tutored read of Pride And Prejudice (completed - thread here)

Group read of The Last Chronicle Of Barset (completed - thread here)

Tutored read of Sense And Sensibility (completed - thread here)

Tutored read of The Italian (beginning 2nd May)

Tutored read of Love-Letters Between A Nobleman And His Sister (beginning after The Italian)

Georgette Heyer (April): Faro's Daughter

Agatha Christie (May): Peril At End House

Tutored read of Pride And Prejudice (completed - thread here)

Group read of The Last Chronicle Of Barset (completed - thread here)

Tutored read of Sense And Sensibility (completed - thread here)

Tutored read of The Italian (beginning 2nd May)

Tutored read of Love-Letters Between A Nobleman And His Sister (beginning after The Italian)

Georgette Heyer (April): Faro's Daughter

Agatha Christie (May): Peril At End House

11Matke

Hi, Liz!

I see we're on for Last Chronicle. Glad I stopped by today, as I had forgotten it was scheduled for March.

And Murder at the Vicarage! One of my top five in the Christie bibliography. I may turn up there as well...

I see we're on for Last Chronicle. Glad I stopped by today, as I had forgotten it was scheduled for March.

And Murder at the Vicarage! One of my top five in the Christie bibliography. I may turn up there as well...

13PaulCranswick

>2 lyzard: Because of the relative obscurity of many of the books I read, I tend to get less visitors / conversation than many of the 75-ers, so anyone who drops by this thread can be certain of a welcome bordering on the hysterical.

I am surprised, given the circumstances, that you have left that little statement on your intros.

The "unpopularity" of your thread has been scotched completed in the last couple of months, Liz, and rightly so.

Congratulations on your latest thread. xx

I am surprised, given the circumstances, that you have left that little statement on your intros.

The "unpopularity" of your thread has been scotched completed in the last couple of months, Liz, and rightly so.

Congratulations on your latest thread. xx

15AuntieClio

Hi Liz, love the flowers at the top.

17souloftherose

Happy new thread Liz! I enjoyed Mr Quin a lot so don't worry about that.

#1 Beautiful!

#9 Busy schedule! Is it wrong that I felt excited when I went to the work page for The Corinthian and saw the tag 'cross-dressing'?

#1 Beautiful!

#9 Busy schedule! Is it wrong that I felt excited when I went to the work page for The Corinthian and saw the tag 'cross-dressing'?

18CDVicarage

More beautiful flowers, especially enjoyable as we have a very grey day here today.

20rosalita

Gorgeous orchids! And to respond to your last comment to me on your old thread, I definitely plan to continue the Barset series! In fact, I should just plan to start the next one this month, which is Barchester Towers. I've got an e-omnibus of all 6 novels, happily waiting for me on my Kobo.

21Morphidae

>13 PaulCranswick: Shush. I want my hysterical welcome.

22lyzard

Hi, Barbara, Gail, Lori, Paul, Roni, Steph, Diana, Heather, Kerry, Amber, Julia and Morphy - thank you all so much for visiting! I'm glad you're enjoying my flowers - particularly if they can brighten up what I know for many of you has been a long and difficult winter.

>11 Matke: I hope to have your company for both, Gail.

>13 PaulCranswick: Sez Mr Fourteen-Threads-And-It's-Barely-March. :)

>17 souloftherose: I'm glad of that, anyway!

It depends what kind of cross-dressing you're expecting. :)

>20 rosalita: Thrilled that you're going on with the Barchester novels, Julia. Please do post on the tutored read thread for Barchester Towers if you want or need to.

>21 Morphidae: MORRRRRRRRRRPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! :D

On a more serious note, very sorry to hear of your recent health issues. I hope things are looking up for you.

>11 Matke: I hope to have your company for both, Gail.

>13 PaulCranswick: Sez Mr Fourteen-Threads-And-It's-Barely-March. :)

>17 souloftherose: I'm glad of that, anyway!

It depends what kind of cross-dressing you're expecting. :)

>20 rosalita: Thrilled that you're going on with the Barchester novels, Julia. Please do post on the tutored read thread for Barchester Towers if you want or need to.

>21 Morphidae: MORRRRRRRRRRPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! :D

On a more serious note, very sorry to hear of your recent health issues. I hope things are looking up for you.

23lyzard

Regular visitors would know what it generally means when I set up a new thread - namely, that I'm badly behind with my reviewing and looking for inspiration.

That was certainly the plan yesterday, but I only got so far as setting up the thread before I was taken down by the most awful headache - the kind that only recedes if you lie down with your eyes shut, and so won't even let you read.

Of course, now that it's Monday morning I feel perfectly fine...

That was certainly the plan yesterday, but I only got so far as setting up the thread before I was taken down by the most awful headache - the kind that only recedes if you lie down with your eyes shut, and so won't even let you read.

Of course, now that it's Monday morning I feel perfectly fine...

24lyzard

On the other hand, I had a bit of good book-buying fortune over the weekend. I've been chasing a copy of John Rhode's The Claverton Mystery and found an inexpensive copy listed on a local bidding site. I ended up securing that plus three other books for a total of $29.40 including shipping; the seller was nice enough to combine the latter when she didn't have to. The other three books were not things I was specifically looking for but were old and obscure enough to attract my attention. :)

So---

The Claverton Mystery by John Rhode (1932)

A Woman In Exile by Horace Annesley Vachell (1926)

The Girl From Nowhere by Mrs Baillie Reynolds (1910)

Comin' Thro' The Rye by Helen Mathers (1898)

So---

The Claverton Mystery by John Rhode (1932)

A Woman In Exile by Horace Annesley Vachell (1926)

The Girl From Nowhere by Mrs Baillie Reynolds (1910)

Comin' Thro' The Rye by Helen Mathers (1898)

26rosalita

>22 lyzard: I'm sure I will be making good use of the tutored thread, Liz! I hadn't realized until I checked to make sure I had it starred that it was put up in 2012. Good grief, I'm 2 years behind. :-0

27lyzard

Yike!!

(That's a yike recognising how long I've been doing this, not a yike at where you're up to!)

(That's a yike recognising how long I've been doing this, not a yike at where you're up to!)

28SqueakyChu

Yike!! (from me, too!)

Congrats on your longevity as a tutor...and heartfelt thanks as well!

Is there a "tutored read" thread for 2014? If so, could you point me to it? Thx!

Congrats on your longevity as a tutor...and heartfelt thanks as well!

Is there a "tutored read" thread for 2014? If so, could you point me to it? Thx!

29lyzard

Thanks, Madeline, but as I said to Ilana during Pride And Prejudice, the success of a tutored read rests with the tutee and their willingness to talk and ask questions; responding is the easy bit. :)

Which sadly brings us to your second point---no, I didn't bother this year, because things had pretty much shrivelled down to "just me". Other than Suzanne's leading of Wolf Hall we really couldn't get the concept to work on a broader stage, unfortunately.

Which sadly brings us to your second point---no, I didn't bother this year, because things had pretty much shrivelled down to "just me". Other than Suzanne's leading of Wolf Hall we really couldn't get the concept to work on a broader stage, unfortunately.

30SqueakyChu

:(

31lyzard

Agreed. But it ended up looking like a weird exercise in self-promotion on my part, which was just too uncomfortable.

32lyzard

Having finished The Noose, I was doing a little research into the next title in the Anthony Gethryn series - in correct publication order, having been misled previously over the #3 and #4 series entries - and discovered that Philip MacDonald apparently wrote seven books in 1931. That can't be right - can it!?

ETA: Good grief! Make that eight!

ETA2: No, strike that, we're back to seven...

ETA3: Nope, we're definitely back at eight...

ETA: Good grief! Make that eight!

ETA2: No, strike that, we're back to seven...

ETA3: Nope, we're definitely back at eight...

33Smiler69

>31 lyzard: It might just work as a concept at a different time, as the group dynamic changes with constant flux in the membership base. There are the core members who have been here many many years, and then new people joining, other people leaving. And then reading interests evolving over time too. Might be worth giving the tutored reading concept on a wider scale a try again eventually because it seems like such an amazing feature!

34lyzard

Yes, it's difficult to know how to "advertise" outside the 75ers, which is not necessarily the best place for such a concept, or anyway certainly not the only place.

But then, we got "outsiders" for both Castle Of Wolfenbach and Pride And Prejudice, so hopefully the word is getting out there a little. :)

But then, we got "outsiders" for both Castle Of Wolfenbach and Pride And Prejudice, so hopefully the word is getting out there a little. :)

35Smiler69

Well, perhaps it might be worth starting a separate group for it eventually so it's readily available LT-wide? Something else to think about...

36lyzard

Oh, Philip MacDonald - you prolific nuisance, you! I can't remember the last time I had so many OCD buttons pushed at once!

As far as I have been able to determine - and I *have* determined which is the next book in my series, so at least my breathing has slowed down a little - within a fourteen-month period, Philip MacDonald's publishing activities look something like this:

Persons Unknown - aka and much better known as The Maze - first published in the US late in 1930, republished early in 1931, published in the UK in 1932, which is usually, incorrectly, listed as its publication date; an Anthony Gethryn story and therefore the next in my series (Book #5).

The Wraith - 1931 (Book#6)

The Crime Conductor - published late 1931 in the US, early 1932 in the UK (Book #7)

Murder Gone Mad - 1931 - sort of a standalone, except that Anthony Gethryn gets name-checked and the main detective is a character who often appears in the Gethryn mysteries as a supporting character, leaving me to ponder if he should be considered an independent series character or not

Mystery At Friar's Pardon - 1931 - either a standalone or the first in a short series, published as by "Philip MacDonald" in the UK and as by "Martin Porlock" in the US

The Choice aka The Polferry Mystery aka The Polferry Riddle - 1931 - a standalone mystery

Harbour - 1931 - a standalone mystery published as by "Philip MacDonald" in the UK and by "Anthony Lawless" in the US

Moonfisher - 1931 - a horsey romance published as by "Anthony Lawless"

As far as I have been able to determine - and I *have* determined which is the next book in my series, so at least my breathing has slowed down a little - within a fourteen-month period, Philip MacDonald's publishing activities look something like this:

Persons Unknown - aka and much better known as The Maze - first published in the US late in 1930, republished early in 1931, published in the UK in 1932, which is usually, incorrectly, listed as its publication date; an Anthony Gethryn story and therefore the next in my series (Book #5).

The Wraith - 1931 (Book#6)

The Crime Conductor - published late 1931 in the US, early 1932 in the UK (Book #7)

Murder Gone Mad - 1931 - sort of a standalone, except that Anthony Gethryn gets name-checked and the main detective is a character who often appears in the Gethryn mysteries as a supporting character, leaving me to ponder if he should be considered an independent series character or not

Mystery At Friar's Pardon - 1931 - either a standalone or the first in a short series, published as by "Philip MacDonald" in the UK and as by "Martin Porlock" in the US

The Choice aka The Polferry Mystery aka The Polferry Riddle - 1931 - a standalone mystery

Harbour - 1931 - a standalone mystery published as by "Philip MacDonald" in the UK and by "Anthony Lawless" in the US

Moonfisher - 1931 - a horsey romance published as by "Anthony Lawless"

37lyzard

>35 Smiler69: Yes, that's something to think about. When we start Sense And Sensibility I might put that out for discussion.

40Smiler69

Yes, the funny thing about the TIOLI listing is that I doubt very much I'll finish it in March considering the time it took me to get through P&P!

41harrygbutler

>36 lyzard: As a fan of many older mysteries, I've been enjoying your posts. Thanks for sharing! The Polferry Riddle is not a standalone, but part of the Anthony Gethryn series. My Crime Club edition names him on the title page, and he has already shown up early in Ch. 2 (I had just started reading it this evening).

42lyzard

Hello, Harry - thank you so much for visiting!

I bow down before your personal knowledge of The Polferry Riddle - your statement completely contradicts most of what is asserted out there in internet-land. Thanks for dropping in with that piece of information, it's much appreciated! It seems impossible that MacDonald would have published four Gethryn novels in one year, but that's how it seems to be falling out - unless you know better?? :)

I bow down before your personal knowledge of The Polferry Riddle - your statement completely contradicts most of what is asserted out there in internet-land. Thanks for dropping in with that piece of information, it's much appreciated! It seems impossible that MacDonald would have published four Gethryn novels in one year, but that's how it seems to be falling out - unless you know better?? :)

43harrygbutler

Unfortunately, I don't really know more. I'm not surprised by the quantity written, but I'm a bit surprised that all were published within such a short period.

In case it helps in sorting out the order, I'll note that the last book listed before The Polferry Riddle in my copy (a rather battered first edition, per the publishing information) is Persons Unknown, which appears fifth in the list, with The Polferry Riddle sixth.

In case it helps in sorting out the order, I'll note that the last book listed before The Polferry Riddle in my copy (a rather battered first edition, per the publishing information) is Persons Unknown, which appears fifth in the list, with The Polferry Riddle sixth.

44lyzard

That is helpful - it confirms what I thought I knew from scrambling around in copyright databases. (Yes, I'm that obsessive!)

If he was churning out books at such a frantic rate, you can understand why his publisher might have wanted to "hide" one or two behind a pseudonym.

If he was churning out books at such a frantic rate, you can understand why his publisher might have wanted to "hide" one or two behind a pseudonym.

45SqueakyChu

>31 lyzard: >37 lyzard:

But it ended up looking like a weird exercise in self-promotion on my part

I understand, but what a disappointment. Drneutron did that great tutorial with bell7 in the past as well.

So where do you keep a running list of own your tutorial schedule? If someone else later wants to be a tutor, how do they do that?

it's difficult to know how to "advertise" outside the 75ers

How about asking Loranne to put it into one of our State of the Thing newsletters? If you do that, set up the Tutored Read group first so others can first join, then follow what comes next.

The good thing about a group is that you could use actual messages to convey information rather than a wiki page (which some people either can't find or easily use).

I know this would be taking it outside of the 75ers group, but that would not be a bad thing.

>35 Smiler69: >38 Smiler69: >40 Smiler69:

separate group for it

Ilana, I like that idea. At least I'd know where to look for this information.

I think we might have quite a few people following along on that one.

Even me! Tee hee!!

the funny thing about the TIOLI listing is that I doubt very much I'll finish it in March

I'm known for moving most of my tutored reads from one month to the next month in the TIOLI challenges. :D

But it ended up looking like a weird exercise in self-promotion on my part

I understand, but what a disappointment. Drneutron did that great tutorial with bell7 in the past as well.

So where do you keep a running list of own your tutorial schedule? If someone else later wants to be a tutor, how do they do that?

it's difficult to know how to "advertise" outside the 75ers